Boxing’s historical trajectory in Milwaukee paralleled its rise and fall on the national scene. Local fascination with prizefighting faded in the second half of the twentieth century, although amateur boxing has continued into the twenty-first century.[1]

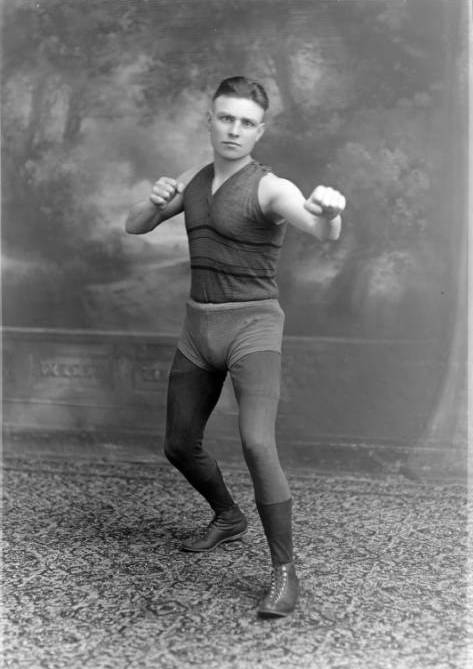

The popularity of boxing grew in Milwaukee during the second half of the nineteenth century. At the time, boxing was a disorganized period of bare-knuckle fights that often resulted in permanent injuries and public outrage.[2] The Marquess of Queensberry rules, drafted by Welshman John G. Chambers in 1867 and thereafter universally adopted, made gloves mandatory and established the ten-second knockout clock. These reforms helped temper opposition to the sport.[3] Between 1869 and 1913, prizefighting was illegal in Milwaukee, but local authorities often turned a blind eye and allowed clandestine matches to take place.[4] By 1915, boxing had undergone a certain degree of professionalization, with the State Athletic Commission licensing clubs and referees and requiring fighters to undergo physical examination before stepping into the ring—all in an effort to quell public criticism.[5] Questions still remained, however, about just who could box in Milwaukee, and participation remained limited, for the most part, to white fighters.[6]

By the time Jack Johnson became the first black world heavy-weight champion in 1908, ushering in the search for the “Great White Hope,” Milwaukee had established itself as one of the nation’s top boxing venues.[7] Walter H. Liginger, of the Milwaukee Athletic Club, spearheaded the effort to keep African Americans out of the ring until he permitted a boxer named “Tiger” Flowers to fight local (white) phenomenon Henry “King Tut” Tuttle in 1930.[8] On April 11, nearly 8,000 spectators at the Auditorium witnessed the fall of the color barrier in Milwaukee.[9] Professional boxing continued to attract huge crowds in Milwaukee through the 1960s. An estimated 135,000 people attended a lakefront bout between Cowboy Billy Pryor and Tony Zale in Juneau Park in 1941, while TMJ also broadcast the fight.[10] The time and place represented the apex of pro boxing’s appeal in Milwaukee. Since then, the amateur rings have maintained the sports presence in the area.[11]

The mid-twentieth century also witnessed amateur boxing’s glory days in Milwaukee.[12] Since the early 1930s, the Wisconsin Golden Gloves tournaments have been the state’s premier amateur boxing event.[13] Sponsored and promoted by the Milwaukee Journal between 1937 and 1955, the series attracted several hundred amateur fighters and drew tens of thousands to the Milwaukee Auditorium and the Eagles Club in the 1950s and 1960s.[14]

Boxing’s popularity at both the professional and amateur levels has declined since the 1960s. Local boxing historian Pete Ehrmann has pointed to poor promotion, substandard coaching, and inconsistent governance.[15] At the same time, critics continue to emphasize the danger posed by frequent head injuries, further clouding the sport’s future.[16] As a fringe activity, boxing in Milwaukee endures in places such as former boxer Israel Acosta’s United Community Center and the late Al Moreland’s Northside gyms, which afford inner city youth a chance to learn the sport.[17]

Footnotes [+]

- ^ Paul Calhoun, “Lure of the Ring” Milwaukee Magazine (August 1995): 56.

- ^ Ellen Langill and Dave Jensen, The Greater Milwaukee Story (Milwaukee: Milwaukee Publishing Group, 1996), 43-44.

- ^ Pete Ehrmann, “Remembering Boxing’s Fantastic, and Illegal, Return to Milwaukee,” OnMilwaukee.com, April 28, 2014, accessed June 1, 2014. The rules, according to local boxing historian Pete Ehrmann, also banned biting, kicking, gouging, and other objectionable tactics. See also Michael Gartner, “Words,” The Milwaukee Journal, November 9, 1989, accessed June 1, 2014, http://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=1499&dat=19891109&id=OmYaAAAAIBAJ&sjid=9SsEAAAAIBAJ&pg=3722,1405160

- ^ Ehrmann, “Remembering Boxing’s Fantastic, and Illegal, Return to Milwaukee.”

- ^ « Boxing Put on High Plane in Wisconsin, Says Commission in Annual Report,” The Milwaukee Sentinel, January 10, 1915, accessed June 3, 2014, http://news.google.com/newspapers?id=8R9QAAAAIBAJ&sjid=lgoEAAAAIBAJ&pg=3994%2C3114567

- ^ Pete Ehrmann, “Breaking the Boxing Color Barrier,” OnMilwaukee.com, November 30, 2013, accessed June 1, 2014.

- ^ Pete Ehrmann, “Flowers a Pioneer in Milwaukee Boxing,” February 28, 2013, last accessed July 10, 2017; Gerald Early, “Rebel of the Progressive Era,” PBS.org, January 2005, accessed June 5, 2014.

- ^ Pete Ehrmann, “Flowers a Pioneer in Milwaukee Boxing”; Milwaukee Journal, September 19, 1924. The Commission allowed one match between black fighters in 1918 because the proceeds went to the Red Cross. King Tut lost the fight after fouling Flowers with an unintentional low punch in the fifth round.

- ^ Pete Ehrmann, “Flowers a Pioneer in Milwaukee Boxing.”

- ^ Pete Ehrmann, “Super Crowds Marked ‘Man of Steel’—Tony Zale’s 1941 Lakefront Bout,” OnMilwaukee.com, August 15, 2012, accessed June 2, 2014; “Crowd of 135,000 Fills Lake Front for Convention’s Free Boxing Show,” The Milwaukee Journal, August 17, 1941, accessed June 1, 2014, http://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=1499&dat=19410817&id=Lu8ZAAAAIBAJ&sjid=6CIEAAAAIBAJ&pg=2839,187241

- ^ Calhoun, “Lure of the Ring,” 56.

- ^ Calhoun, “Lure of the Ring,” 56.

- ^ Pete Ehrmann, “Golden Gloves Gives the Local Boys a Fight for Boxing Glory,” OnMilwaukee.com, March 31, 2012, accessed June 1, 2014.

- ^ Pete Ehrmann,“A Look back at Dave Ragus and Golden Gloves Heyday,” OnMilwaukee.com, April 2, 2010, accessed June 1, 2014; Gary D’Amato, “Wisconsin Golden Gloves Trying to Get off the Mat,” Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, April 11, 2012, accessed June 1, 2014; Kevin Meagher, “Fight Club,” Media Milwaukee website, December 22, 2011, accessed June 1, 2014, http://www4.uwm.edu/mediamilwaukee/sports/fight-club.cfm; Pete Ehrmann, “Recalling Eddie Brooks’ Once Golden Gloves,” OnMilwaukee.com, April 4, 2014, accessed June 1, 2014. The first tournament was in 1930.

- ^ Kevin Meagher, “Fight Club.”

- ^ “Boxing at Your Own Risk: Neurologists Reassess Brain’s Vulnerability,” April 1, 2013, accessed June 1, 2014; “Analysis: Children as Young as Eight Years Old Competing in Amateur Boxing Tournaments in Wisconsin,” Weekend Edition Saturday, National Public Radio, May 8, 2004, accessed May 20, 2014.

- ^ James E. Causey, “Al Moreland Fought for the Kids of Milwaukee,” Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, August 21, 2009, accessed June 1, 2014; Calhoun, “Lure of the Ring,” 56.

For Further Reading

Calhoun, Paul. “Lure of the Ring.” Milwaukee Magazine. August 1995: 52-59.

Pete Ehrmann’s blogs, OnMilwaukee.com, at http://onmilwaukee.com/myOMC/authors/peteehrmann/ronmarshobituary.html.

0 Comments

Please keep your community civil. All comments must follow the Encyclopedia of Milwaukee Community rules and terms of use, and will be moderated prior to posting. Encyclopedia of Milwaukee reserves the right to use the comments we receive, in whole or in part, and to use the commenter's name and location, in any medium. See also the Copyright, Privacy, and Terms & Conditions.

Have a suggestion for a new topic? Please use the Site Contact Form.