The Clement J. Zablocki VA Medical Center is the direct descendant of the Northwestern Branch of the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers (NHDVS), established by Congress in 1865 to care for Union soldiers who had suffered disabling wounds or illnesses due to their service in the Civil War. The home was funded partly by $100,000 raised at a Sanitary Fair organized by the women of the West Side Soldiers’ Aid Society. A number of prominent Milwaukeeans were involved with creating and expanding the home, including John Lendrum Mitchell, on whose land the home was built, and architects Edward Townsend Mix and Henry C. Koch, who designed a number of the buildings. The NHDVS was absorbed by the newly formed Veterans Administration (VA) in 1930 and, as the emphasis evolved from providing housing to providing extensive medical and rehabilitation care for veterans of the First and Second World Wars, the facility added numerous medical and research facilities. It was renamed in 1984 in memory of Clement J. Zablocki (1912-1983), the Milwaukee-area Congressman who had long advocated on behalf of the hospital. The original buildings—including the main building, several barracks, the Ward Theater, the chapel, and the administration building—were designated a Historic District and placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2005. It also on the Wisconsin State Register of Historic Places and, in 201l was named a National Historic Landmark, along with surviving structures from other branches of the NHDVS.[1]

The NHDVS was part of a massive expansion of federal responsibility for the care of veterans, which before the Civil War had consisted of small pensions for volunteers in the Revolutionary War, the War of 1812, and the Mexican-American War, as well as two small residential homes for disabled sailors and soldiers who had served for at least twenty years. The scope of the problem facing the United States government in 1865—with over 2,000,000 veterans, tens of thousands of whom were unable to support themselves—led to the creation of a massive pension system and of the NHDVS. (Originally called the National Asylum, the name was changed in 1873.)[2]

The first four branches of the system, located in Milwaukee, (the Northwestern Branch); Dayton, Ohio (the Central Branch); Togus, Maine (the Eastern Branch); and Norfolk, Virginia (the Southern Branch) were up and running by 1870. There were a total of eleven branches by 1929. Although Civil War soldiers dominated the population at the homes, a few veterans of the War of 1812 and Mexican War were also admitted, and by 1884, eligibility was expanded to any veteran who had any kind of disability. Disabled veterans of the Spanish-American War began entering the homes in 1900. Although the NHDVS was officially integrated, relatively few African American veterans actually lived in the homes. As the population at the homes changed from “old soldiers” to young veterans of the First World War needing short-term medical or psychiatric care, the NHDVS began shifting from a residential institution to a hospital. That transition was completed when the NHDVS system was subsumed by the VA in 1930.[3]

The Northwestern Branch of the NHDVS opened with a handful of residents in May 1867 on a 400-acre site west of Milwaukee, linked to Milwaukee by a short train ride or a half-hour journey in a horse-drawn buggy. The federal reservation—which included a post office—was called Wood, and included a cemetery and, by the late twentieth century, other services for veterans.[4]

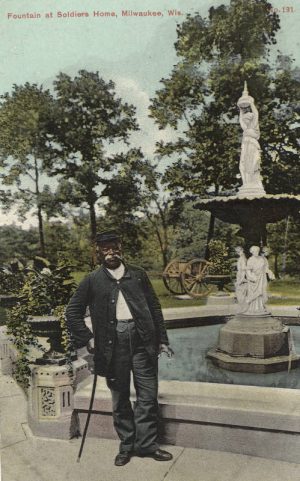

By the 1890s, over 2,000 men lived at the home. Like the other branches of the NHDVS, the Northwestern Branch was beautifully landscaped with forests, lakes, and winding parkways. In addition to barracks and hospitals, the homes featured libraries, theaters, beer halls, and other recreational facilities. During its days as a home for Civil War soldiers, the Northwestern Branch entertained tens of thousands of tourists every year; the grounds also hosted Milwaukee’s July Fourth celebration in the 1870s and 1880s. However, clustered near both the northern entrance (at Spring Street, now Wisconsin Ave.) and the southern entrance (on National Avenue, named after the home) were taverns frequented by the old soldiers, which caused health and disciplinary problems on and off the home grounds.[5]

The affiliation of the Northwestern Branch with the Veterans Administration resulted in a name change to Wood Veterans Hospital. The 1930s saw an expansion of the hospital by more than 200 beds, while the Second World War dramatically increased both the demands on and funding for VA hospitals. Wood added treatment for spinal injuries, paralysis, and other severe disabilities and, in 1946, contracted with the Marquette University Medical School to accept residents for medical training (the placement of residents continued when the MU Medical School spun off from the university to form the Medical College of Wisconsin). The 1950s and 1960s saw the hospital add a research component to its mission; by 1965 the budget included half a million dollars for research, especially into anesthesia and respiratory and lung diseases. A new Nursing Home Care Unit was established in 1965.[6]

A new, ten-floor hospital—which Rep. Zablocki had advocated since the early 1950s—finally opened in 1966. It was located just south of the original NHDVS buildings, which continued to be used by the VA. The hospital’s budget doubled over the next twenty years, with the expansion of out-patient services, memory care for geriatric veterans, and research programs in immunology and in the treatment of spinal cord and other injuries. The 1990s saw the creation of the Women’s Primary Care Clinic—the first major effort to serve female veterans, as well as the opening of the Rehabilitation Robotic Research and Design Laboratory, a crash test lab, and a new spine center. By 2014, with an aging population of Vietnam War era veterans and new patients created by the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, the Zablocki VA Medical Center treated 61,000 patients—in Wood and at four out-patient clinics in southeastern Wisconsin—and employed over 4,000 medical professionals and other staff.[7]

Footnotes [+]

- ^ Patricia A. Lynch, Milwaukee’s Soldiers Home (Mount Pleasant, SC: Arcadia Publishing, 2013), 8; “Zablocki, Clement John, (1912-1983),” Biographical Directory of the United States Congress, last accessed June 8, 2017; “National Register of Historic Places,” National Park Service, last accessed June 8, 2017; “Wisconsin State Register of Historic Places,” Wisconsin Historical Society, last accessed June 8, 2017; Lynch, Milwaukee’s Soldiers Home, 9.

- ^ “History of the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers,” NPS.Gov, , last accessed June 8, 2017.

- ^ “History of the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers.”

- ^ James Marten, “A Place of Great Beauty, Improved by Man: The Soldiers’ Home and Victorian Milwaukee,” Milwaukee History 22 (Spring 1999): 2-15.

- ^ “History of the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers”; Marten, “A Place of Great Beauty, Improved by Man”; James Marten, “Nomads in Blue: Disabled Veterans and Alcohol at the National Home,” in David A. Gerber, ed., Disabled Veterans in History (Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 2000), 275-294.

- ^ Dozen Decades of Dedication, 1867-1987: Milwaukee in Service of the Veteran (Milwaukee: The Center, 1987), 16, 17, 25.

- ^ Dozen Decades of Dedication, 17, 20; “VA Offering to Help Military Women,” Milwaukee Business Journal, March 14, 2010; Guy Boulton, “Zablocki Ranks Better than VA Peers in Patient Satisfaction, Wait Times,” Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, June 21, 2014.

For Further Reading

Kelly, Patrick J. Creating a National Home: Building the Veterans’ Welfare State, 1860-1900. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1997.

Leahy, Stephen M. The Life of Milwaukee’s Most Popular Politician, Clement J. Zablocki: Milwaukee Politics and Congressional Foreign Policy. Lewiston, N.Y.: E. Mellen Press, 2002.

Lynch, Patricia A. Milwaukee’s Soldiers Home. Mount Pleasant, SC: Arcadia Publishing, 2013.

0 Comments

Please keep your community civil. All comments must follow the Encyclopedia of Milwaukee Community rules and terms of use, and will be moderated prior to posting. Encyclopedia of Milwaukee reserves the right to use the comments we receive, in whole or in part, and to use the commenter's name and location, in any medium. See also the Copyright, Privacy, and Terms & Conditions.

Have a suggestion for a new topic? Please use the Site Contact Form.