Throughout Milwaukee’s history, firms of different sizes preserved, processed, and packaged raw ingredients from Wisconsin farms, producing an array of foodstuffs, including alcoholic beverages, baked goods, candy, and ice cream. Many of these specialties derived from skills that pioneer settlers and later immigrants brought with them and developed over time.

Production and preservation of food in early Milwaukee was largely done in the home. Early residents typically maintained vegetable gardens and domestic animals in their yards, thereby providing food items that were either fresh or preserved through canning, fermenting, salting, or smoking.[1] Home food processing practices continued with various degrees of interest throughout the city’s history. Even in the beginning, however, a few firms took on these chores as home consumers increasingly desired the convenience and uniformity of mass-produced food products.

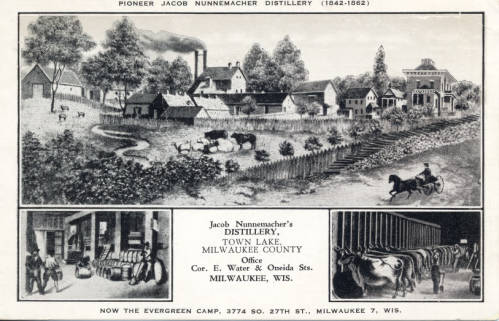

Among the earliest forms of commercial food processing in Milwaukee was the production of alcoholic beverages. In 1840, Welsh immigrants Richard G. Owens, William Pawlett, and John Davis established the city’s first brewery and distillery on Huron Street (now E. Clybourn) near the lake. Importing grains and hops, first from sources on the East Coast and later from local farms, Owens, Pawlett, & Davis produced both beer and whiskey for local drinkers.[2] Their legacy inspired the brewing industry, a key institution in Milwaukee’s economy and future identity.

Distilling became a fruitful endeavor in the years following the Civil War, producing mostly whiskey, rye, and later gin. Milwaukee distillers went from producing 3,046 barrels of such “highwines” in 1865 to 43,175 by 1876.[3] Stricter federal regulation and growing competition from Chicago firms temporarily weakened Milwaukee’s liquor production in the late 1870s and 1880s.[4] However, the industry recovered with even greater strength in following decades. In 1891, Milwaukee’s 20 distillers netted approximately $1.5 million in sales. By 1912, a reported 57 firms earned nearly $9.9 million in sales.[5]

Among the most prominent Milwaukee liquor producers was the Meadow Springs Distillery. Established by a group of German entrepreneurs in 1882, Meadow Springs opened its main plant in the Menomonee River Valley and produced 180,000 gallons of whiskey by the end of that year.[6] In 1887, the company changed its name to National Distillery, making a variety of whiskeys and gins. Along the way, it expanded into the production of household and commercial yeast products, under the Red Star label, as well as the distillation of vinegar.[7]

While brewing was large enough as an industry to survive Prohibition, most liquor producers closed permanently. National Distillery, however, shifted its focus completely to its yeast and vinegar operations, changing its name to Red Star Yeast and Products in 1919. The company resumed distilling gin after Prohibition ended in 1933, but remained primarily concentrated on its new base products. In the decades following the Second World War, Red Star acquired other food companies and diversified its product lines. The company changed its name to Universal Foods in 1962 and to Sensient Technologies in 2000, selling its Red Star division to the French yeast producer Lesaffre in 2001. The Red Star Yeast plant remained a fixture in the Menomonee River Valley, with its odors familiar to I-94 commuters, until it closed in 2005.[8]

In recent years, distilling has experienced a “craft” renaissance in Milwaukee similar to that of brewing. In 2004 Guy Rehorst established the first such craft operation, the Great Lakes Distillery, in Riverwest. In 2008 the company moved into a larger space in Walker’s Point, where it produces small batches of vodka, gin, rum, and a variety of other spirits that are distributed throughout the region.[9] Other craft distillers, like Central Standard and Twisted Path (both of which opened in 2014), have since joined Great Lakes in Milwaukee.[10]

Unlike beer and liquor, wine was an import product for most of Milwaukee’s history. Since the 1990s, however, a number of small wineries have emerged, producing an array of wines from various grapes (predominantly imported from other parts of the United States and the world) and local fruits, such as cherries, cranberries, elderberries, and strawberries. Among the first Milwaukee-area wineries was the Newberry (later Stone Mill) Winery of Cedarburg. Opened by a local home-winemaker Jim Pape in an old woolen mill in the early 1970s, the Newberry winery was best known for its cherry wines. The Prairie du Sac-based Wollersheim Winery purchased the operation in 1990, changing its name to the Cedar Creek Winery and expanding its products into grape-based varieties.

Another significant, early form of commercial food processing in Milwaukee was the milling of wheat and other grains into flour. John Anderson and Dr. E. B. Wolcott established the city’s first flourmill on the Rock River Canal in 1844, followed closely by others who also took advantage of the waterpower generated by the newly constructed North Avenue Dam. Flour milling steadily grew into a key Milwaukee industry through the mid-to-late nineteenth century, largely benefitting from the city’s thriving grain trade and the transition from water- to steam-powered mills.[11]

Milwaukee flour was used in the homes of local consumers as well as in other regional, national, and international markets. Importantly, it became a key ingredient in the formation of the city’s baking industry. Who opened Milwaukee’s first commercial bakery is unclear, but the industry thrived in small shops that emerged in neighborhoods throughout the city from as early as the 1840s.[12] These operations often specialized in baked goods—such as rye or Italian bread, hard rolls, schnecken, and paczki—that were traditional to the ethnic communities from which they originated.[13] Prior to the advent of affordable household ovens, many of these shops offered their baking equipment to nearby residents, who made their own dough at home.[14]

A few of these smaller shops developed into larger industrial operations over time, moving into the production of more shelf-stable items that could be sold at local grocers and later supermarkets. Among the first to expand into industrial operations were cracker and cookie bakers. By the 1880s, for instance, Robert A. Johnston had transformed the bakery his father, Alexander Johnston, established in Milwaukee in 1848 into one of the city’s largest cracker bakeries. In 1890, the Johnston operation merged with other large regional bakers into the American Biscuit Company (what would later become Nabisco).[15] Johnston returned to industrial baking in 1899, establishing the Robert A. Johnston Company, which made crackers, cookies, chocolate, and other food items—first in Walker’s Point and later in West Milwaukee. The Johnston family sold the company to New York-based Ward Foods in 1969. Changing hands a few times in later decades, the company still remains a fixture in the city’s food industry as the Masterson Company, making a variety of different products, including ice cream and cake ingredients, and toppings.[16]

Other small bakeries also developed into large wholesale bread producers. After working as a baker’s apprentice upon his arrival in Milwaukee in 1856, Austrian immigrant Oswald Jaeger established a bakery on Third Street in 1879. Moving to a new location on Somers Street in 1881, the Jaeger bakery gradually grew into a major wholesale bread operation that by the 1930s supplied local and regional grocers.[17] By the 1960s, the Jaeger Company had become the largest industrial bread bakery in the city, employing 485 workers.[18] The Jaeger family sold the company to Chicago-based Beatrice Foods in 1968, but the Somers Street plant remained in operation through a number of sales and mergers until the Sara Lee Corporation closed its doors in 2005.[19]

Changes in consumer habits hurt both small and large bakeries in Milwaukee by the late twentieth century. Smaller neighborhood bakeries closed, failing to compete with the national wholesale companies that supplied the same supermarkets consumers increasingly relied upon for their food shopping. As the national baking industry consolidated, more modern and centrally located plants served larger markets, gradually replacing Milwaukee’s local producers.[20] Yet, a few Milwaukee area firms, such as baked snack producer Gardetto’s and wholesale bread baker Brownberry, bucked this trend, developing into major producers of baked goods in the late twentieth century. They remain to this day as divisions of major national food corporations.[21] Peter Sciortino’s Bakery on Brady Street, National Bakery and Deli on South Sixteenth Street, and other small shops continue to preserve the city’s neighborhood bakery tradition. Moreover, the industry found new life in the bakeries and tortilla-makers that serve Milwaukee’s growing Latino population. José Lopez opened some of the city’s first Latino bakeries on the South Side in the 1970s—many of which remain significant fixtures in the community to this day.[22] Establishing Super Mercado El Rey on what is now South Cesar E. Chavez Drive in 1978, the Villarreal family began producing tortillas in their store. As demand grew by the late 1990s, El Rey Foods opened a factory on South Muskego Avenue, producing tortillas, tamales, corn chips, and tostadas for distribution to local restaurants, as well as regional, national, and international markets.[23]

While perhaps not nearly as iconic to the city’s economy and identity as brewing, baking, and meatpacking, a number of other various food industries developed long-standing traditions in Milwaukee as well. For instance, the city became home to a notable candy and chocolate industry that grew out of small neighborhood confectionaries in the mid-to-late nineteenth century. By the turn of the century, a few enterprising confectioners manufactured candy and chocolate on larger scales for regional and national markets.[24] In 1880, there were four confectioners in the city that employed 160 workers. The industry grew to 12 firms employing 1,600 workers by 1912 and 26 firms employing 3,147 by 1920.[25] In his 1922 city history, William George Bruce boasted: “According to population, [Milwaukee] makes more candy and chocolates than any other city in the United States.”[26]

Among the largest of Milwaukee’s historic candy-makers was the George Ziegler Candy Company. The company originated in the confectionary of John and Andrew Boll, established in 1861. Taking their brother-in-law George Ziegler on as a partner in Boll Brothers & Company, they moved to a larger location on Grand Avenue in 1865. Ziegler renamed the firm the George Ziegler Candy Company following the retirement of Andrew Boll in 1870 and death of John Boll in 1873. After fire destroyed the company’s Grand Avenue location in 1882, Ziegler moved his operations into a large facility on East Water Street and expanded into national markets.[27] Having relocated once more to a large plant on Florida Street by the turn of the century, the Ziegler Company “had grown to be the largest in its line west of Philadelphia.”[28] This company may have been the first candy-maker to produce a milk-chocolate bar with peanuts in the early 1900s and the first to market an individually wrapped candy bar in 1911.[29] In 1971, the Ziegler family sold the company to Medical Systems, Inc., but the plant closed in 1974 after experiencing financial difficulty.[30] However, Ziegler brands live on today, sold by Half Nuts, a small shop that Bill and Mary Ziegler established in West Allis in 1990.[31]

Other confectioners, like John Luick, went into the production of ice cream. Having worked for local confectioners prior to serving in the Civil War, Luick opened his own shop after he returned home. Originally offering a variety of items, including cakes catered for weddings and parties, Luick eventually focused his operation on the production of ice cream, establishing a large manufacturing plant on Ogden Street by the turn of the century.[32] Luick’s son, William, took over the firm after his father’s retirement in 1903, expanding the company into one of the largest ice cream producers in the United States.[33] The Luick Ice Cream Company merged with the National Dairy Products Corporation in 1926, and moved to a larger, more modern facility on N. Holton Avenue and E. Capitol Drive in 1951.[34] In the following decades, National Dairy Products changed its name to Kraftco, and changed the Luick Co. name to Sealtest to match the parent company’s ice cream division. Kraftco closed the Milwaukee plant in 1972.[35]

Largely growing out of the brewing industry, Milwaukee became home to a number of soda producers as well. Several of the city’s small, pioneer breweries—particularly those that specialized in German weiss beer—also developed lines of root beer and carbonated mineral waters. A few of these breweries later focused their operations solely on the production and packaging of sodas. Established on National Avenue in 1873 and moving to a larger facility on Greenfield Avenue in 1883, the brewery of John Graf became one of Milwaukee’s largest and most notable soda-makers.[36] The Graf family sold the company to the locally based P&V Atlas Corporation in 1968, and the company changed hands several times until the Chicago-based Canfield’s Beverage Company closed the Milwaukee plant in 1985. Graf’s brands, including “Grandpa Graf’s Root Beer” and “50/50,” live on in the Canfield portfolio, now owned by the Dr. Pepper Snapple Group. Milwaukee’s historic brewery-soda tradition remains alive in the many soda varieties produced by the Sprecher Brewing Company.[37]

Milwaukee’s strong ethnic ties also prompted the development of companies that produced a variety of picked foods—from sauerkraut to herring and, of course, pickled cucumbers.[38] In 1932, for instance, Lena “Ma” Baensch established a business in her home, making pickled herring for friends and neighbors. By 1945, Baensch distributed to local grocers, and moved to the company’s current location on E. Locust Street and N. Humboldt Avenue—an old Patrick Cudahy warehouse. The Baensch family sold the company to Kim Wall in 1999, but Ma Baensch brand pickled herring remains a steadfast New Years’ tradition for many Milwaukee families to this day.[39]

Although more recent in origin, other notable firms like Penzey’s Spice Company, Colectivo Coffee Roasters, and Rishi Tea are the latest incarnations in a long history of spice, coffee, and tea processing in Milwaukee. These industries can trace their origins to the pioneer mills that were established in the city in the 1850s and 1860s, like the Flint Brothers’ Star Mills. These firms roasted and ground coffee, milled and mixed spices, and produced tea blends and baking powders, among other items.[40] While nineteenth century mills largely produced for local consumers, Milwaukee’s contemporary spice, coffee, and tea producers have expanded into regional and national markets.

Footnotes [+]

- ^ For instance, John G. Gregory claims that the stepmother of Mrs. Angeline Hill was “the first white woman to bake bread” in the frontier settlement in the late 1830s, attracting great interest from their native neighbors. John G. Gregory, History of Milwaukee, Wisconsin, vol. 2 (Chicago and Milwaukee: S.J. Clarke Publishing, 1931), 1244-1246.

- ^ This brewery was known as the Milwaukee Brewery and later the Lake Brewery but was also commonly referred to as the Owens Brewery. Bayrd Still, Milwaukee: The History of a City (Madison WI: State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1948), 64; One Hundred Years of Brewing (Chicago and New York: H.S. Rich & Co, 1903; repr., New York: Arno Press, 1974), 212; Jerry Apps, Breweries of Wisconsin (Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press, 1992), 16; Wayne L. Kroll, Badger Breweries: Past and Present (Jefferson, WI: Wayne L. Kroll, 1976), 78, 83; John Gurda, Miller Time: A History of the Miller Brewing Company, 1855-2005 (Milwaukee: Miller Brewing Company, 2005), 18.

- ^ Milwaukee Chamber of Commerce, Nineteenth Annual Report on the Trade and Commerce of Milwaukee (Milwaukee: Cramer, Aikens & Cramer, 1877), 118.

- ^ Martin Hintz, A Spirited History of Milwaukee Brews & Booze (Charleston SC: The History Press, 2011), 60.

- ^ Milwaukee Grain & Stock Exchange, Fifty-Fourth Annual Report of the Chamber of Commerce of the City of Milwaukee (Milwaukee: Radtke Bros. & Kortsch, 1912), 71-72.

- ^ Hintz, A Spirited History of Milwaukee Brews & Booze, 61-63; John Gurda, “Red Star Era Ends at Valley Complex,” JSOnline, March 31, 2012.

- ^ Hintz, A Spirited History of Milwaukee Brews & Booze, 65; Gurda, “Red Star Era Ends at Valley Complex.”

- ^ Gurda, “Red Star Era Ends at Valley Complex.”

- ^ Hintz, A Spirited History of Milwaukee Brews & Booze, 68-76.

- ^ Tom Daykin, “Central Standard Distillery Brings Spirits to Walker’s Point,” JSOnline, June 12, 2014; “About,” Twisted Path Distillery, http://twistedpathdistillery.com/about.html, accessed February 10, 2016, now available at http://www.twistedpathdistillery.com/about/, last accessed May 31, 2017.

- ^ Still, Milwaukee, 63-64; John Gurda, The Making of Milwaukee (Milwaukee: Milwaukee County Historical Society, 1999), 118; Margaret Walsh, The Manufacturing Frontier: Pioneer Industry in Antebellum Wisconsin 1830-1860 (Madison, WI: State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1972), 179-182.

- ^ The earliest reference to a commercial bakery can be found in James S. Buck’s Pioneer History of Milwaukee. According to Buck, David House opened a bakery at 291 Lake Street shortly after his arrival to Milwaukee in 1846 and was “among the first to make pilot or sea biscuit.” James S. Buck, Pioneer History of Milwaukee: From the First American Settlement in 1833 to 1841 (Milwaukee: Swain & Tate, 1890), 108.

- ^ Carol Deptolla, “Baked Goods ‘Make Us Swoon,’” JSOnline, March 27, 2012.

- ^ William George Bruce, History of Milwaukee, City and County, vol. 1 (S. J. Clarke Publishing Company, 1922), 759.

- ^ John G. Gregory, History of Milwaukee, Wisconsin, vol. 1 (Chicago and Milwaukee: S.J. Clarke Publishing, 1931), 544; “After Our Bakeries,” Milwaukee Journal, July 1, 1890, sec. 1, 2.

- ^ Gregory, History of Milwaukee, Wisconsin 1:544; “Robert A. Johnston Company Cookie Factory,” Photograph Collection, Wisconsin Historical Society, accessed February 20, 2016; “Milwaukee County Landmarks: West Milwaukee,” Milwaukee County Historical Society, accessed February 20, 2016, http://www.milwaukeehistory.net/historic-sites-2/county-landmarks/search-county-landmarks/west-milwaukee/, now available at https://milwaukeehistory.net/education/county-landmarks/west-milwaukee/; “Ward Foods Buys Firm in Wisconsin,” Milwaukee Sentinel, July 2, 1974, sec. 2, p. 4; “Berglund, Ex-President of Ward-Johnston, Dies,” Milwaukee Sentinel, August 23, 1982, sec. 2, p. 11; Alvin L. Curtis, “Renovation of Johnston Image Truly Topping on the Ice Cream,” Milwaukee Sentinel, February 6, 1985, sec. 2, p. 4; “Company Culture,” Masterson Company, accessed February 20, 2016.

- ^ Megan Daniels, “Oswald Jaeger Baking Company: Home of Butter-Nut Bread,” Razed in Milwaukee website, November 2, 2012.

- ^ “Jaunts with Jamie: One Horse Bakery Is Giant Now,” Milwaukee Sentinel, November 17, 1965, sec. 1, p. 13.

- ^ Lawrence Sussman, “Bread Lines Dwindling,” Milwaukee Journal, April 1, 1984, sec. Business, p. 1, 3; Rich Rovito, “Commercial Bakery Closing Brings End to Local 205,” Milwaukee Business Journal, August 28, 2005.

- ^ Sussman, “Bread Lines Dwindling,” 1, 3.

- ^ Coco Banken, “What’s It Like to Be Part of a Snack Empire?,” A Taste of General Mills, October 9, 2014; Paige Brunclik, “Brownberry—It All Began with One Woman,” Lake Country Now, November 15, 2010, http://www.lakecountrynow.com/news/lakecountryreporter/108162744.html.

- ^ Sophia Boyd, “Legendary Mexican Bakery to Reopen on Lincoln Avenue,” Milwaukee Neighborhood News Service, February 13, 2016.

- ^ Emily Patti, “El Rey: The King of Milwaukee’s Mexican Grocers,” June 29, 2010; “About Us,” El Rey Foods, accessed March 16, 2016.

- ^ Gregory, History of Milwaukee, Wisconsin, 1:544.

- ^ Industrial History of Milwaukee, the Commercial, Manufacturing, and Railway Metropolis of the Northwest (Milwaukee: E. E. Barton, 1886), 65; Milwaukee Grain & Stock Exchange, Fifty-Fourth Annual Report of the Chamber of Commerce of the City of Milwaukee, 71-72; Bruce, History of Milwaukee 1:247.

- ^ Bruce, History of Milwaukee 1:245.

- ^ Industrial History of Milwaukee, 137.

- ^ Gregory, History of Milwaukee, Wisconsin, 1:544; “George Ziegler Candy Co. Racks Up Many Firsts,” Milwaukee Sentinel, June 18, 1950, sec. B, p. 6.

- ^ “George Ziegler Candy Co. Racks Up Many Firsts,” 6; “About Us,” Half Nuts website, accessed February 26, 2016.

- ^ “Joseph Ziegler Dies; Operated City Firm,” Milwaukee Sentinel, November 22, 1971, sec. 1, p. 7; “Old Candy Firm Asks Debt Plan,” Milwaukee Sentinel, August 11, 1972, sec. 2, p. 6; “Ziegler Candy Company Goes Out of Business,” Appleton Post-Crescent, February 4, 1974, 26.

- ^ Molly Snyder, “Customers Crazy for Half Nuts,” OnMilwaukee.com, April 20, 2014; “About Us.”

- ^ Industrial History of Milwaukee, 128-129; William George Bruce, History of Milwaukee, City and County, vol. 3 (S. J. Clarke Publishing Company, 1922), 488.

- ^ Bruce, History of Milwaukee 3:488.

- ^ “Trapp Dairy Co. Unites With Chain Organization,” Milwaukee Journal, December 1927, sec. 2, p. 1; “Luick Firms Plan to Build E. Capitol Dr. Site,” Milwaukee Journal, September 11, 1949, sec. 2, p. 4; “Luick Occupying Its New Quarters,” Milwaukee Journal, February 5, 1951, sec. Local, p. 3; “Start on Luick Million Dollar Plant Addition,” Milwaukee Sentinel, June 8, 1954, sec. 4, p. 3.

- ^ “Sealtest Plant to Be Closed,” Milwaukee Sentinel, December 7, 1972, sec. 2, p. 5.

- ^ Wayne L. Kroll, Badger Breweries Past and Present (Jefferson, WI: Wayne L. Kroll, 1976).

- ^ “Gourmet Sodas,” Sprecher Brewery, accessed February 26, 2016.

- ^ William John Anderson and Julius Bleyer, eds., Milwaukee’s Great Industries: A Compilation of Facts Concerning Milwaukee’s Commercial and Manufacturing Enterprises, Its Trade and Commerce, and the Advantages It Offers to Manufacturers Seeking Desirable Locations for New Or Established Industries (Milwaukee: Association for the Advancement of Milwaukee, 1892), 205-207; Milwaukee Chamber of Commerce, Forty-Eighth Annual Report of the Trade and Commerce of Milwaukee (Milwaukee: Evening Wisconsin, 1906), 57-58; Milwaukee Grain & Stock Exchange, Fifty-Fourth Annual Report of the Chamber of Commerce of the City of Milwaukee, 71-72.

- ^ Tom Daykin, “Ma’s Tradition Expands,” Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, December 31, 2001, sec. D, 1, 2; Molly Snyder, “Ma Baensch’s Changes the Face of Herring,” OnMilwaukee.com, December 17, 2004; Mrinal Gokhale, “Ma Baensch Food Products,” Urban Milwaukee, January 2, 2015; “Ma’s Legend,” Ma Baensch, accessed February 27, 2016.

- ^ Industrial History of Milwaukee, 132-133, 144, 161-162, 202.

0 Comments

Please keep your community civil. All comments must follow the Encyclopedia of Milwaukee Community rules and terms of use, and will be moderated prior to posting. Encyclopedia of Milwaukee reserves the right to use the comments we receive, in whole or in part, and to use the commenter's name and location, in any medium. See also the Copyright, Privacy, and Terms & Conditions.

Have a suggestion for a new topic? Please use the Site Contact Form.