The Milwaukee Art Museum is the largest art museum in Wisconsin.[1] The 341,000 square-foot museum is home to 30,000 works; its world-renowned collections include strengths in “American decorative arts, German Expressionist works, folk and Haitian art, and American art after 1960.”[2] While the institution’s current manifestation as the Milwaukee Art Museum is relatively new, dating back only to 1980, the Museum has a rich history of additions, acquisitions, and changing appearances from the time of the Museum’s origins in 1888.

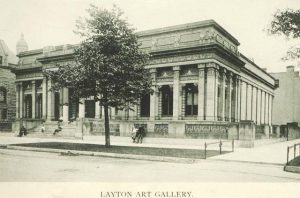

It was in that year that businessman Frederick Layton dedicated the Layton Art Gallery as a gift to the city of Milwaukee. Layton, an integral figure in the development of the meatpacking industry in Milwaukee, was also an avid art collector. Layton donated his art collection and contributed $100,000 to the construction and endowment of Milwaukee’s first art gallery.[3] The same year, the Milwaukee Art Association held its first large public art exhibition.[4] The development of these art institutions reflected the blossoming national museum movement, which by this time had worked its way to the Midwest from the East Coast.[5] In 1911, the Milwaukee Art Association moved its headquarters to Jefferson Street near the Layton Art Gallery. In 1916, the Association officially changed its name to the Milwaukee Art Institute.

After World War II, several women’s groups in Milwaukee wished to support the federal Commission for Living War Memorials, which in 1944 had urged communities to build memorials with practical uses. Three of these groups, Altrusa, Zonta, and the Business and Professional Women’s Clubs decided that Milwaukee should construct a community war memorial and cultural center.[6] Construction on this project began in 1955. The Finnish-American architect Eero Saarinen took over as head architect after the death of his father, with Maynard Meyer of Milwaukee serving as associate architect.[7] The construction of the War Memorial building was completed in 1957. It was in that same year that that the Layton Art Gallery and the Milwaukee Art Institute merged their collections and moved into Saarinen’s 20,000 square-foot Memorial Center, constructed of a “subdued complex of heavy stone and pink-tinted concrete.” [8] It was at this time and in this space that the Milwaukee Art Center was founded.[9]

During the late 1960s, Mrs. Harry Lynde (Peg) Bradley made a contribution of over 600 modern European and American artworks to the Milwaukee Art Center. She also challenged Milwaukeeans to match her million-dollar donation to fund the construction of a new wing for the Milwaukee Art Center to accommodate her paintings. Contributors quickly surpassed the goal, and by 1970, nearly $7 million had been raised.[10] David Kahler of the Milwaukee-based architectural firm, Kahler, Slater & Fitzhugh Scott,[11] was chosen to design the addition. Kahler made a conscious architectural choice to honor the work of Saarinen by blending his 120,000-square-foot addition to complement the aesthetic style of the original War Memorial.[12]

From 1977 until 1984, Gerald Nordland served as the director of the institute. To publically acknowledge and commemorate the increasing role that the Art Center was playing in Wisconsin, the Center was renamed the Milwaukee Art Museum (MAM) in 1980. Three years later, the Milwaukee Art Museum became fully accredited by the American Association of Museums.[13]

MAM received substantial donations during the late 1990s from Jane Bradley Pettit ($13 million) and Betty and Harry Quadracci ($10 million). These donations helped facilitate the construction of an addition that better connected the Museum to the city of Milwaukee.[14] The Spanish-born Santiago Calatrava was chosen as the architect, and the Milwaukee-based construction firm C.G. Schmidt was chosen to build the new addition.[15] The Calatrava was built during a period when many architecturally daring constructions and additions were being commissioned, including the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, Spain, the Contemporary Arts Center in Cincinnati, and the American Folk Art Museum in New York.[16]

The 142,050-square-foot Quadracci Pavilion addition was completed in 2001. This addition includes the Windhover Hall, the grand entrance, with ninety-foot tall glass ceilings. The addition also includes the “Museum’s signature wings,” the Burke Brise Soleil, which is a “moveable sunscreen” made of 72 steel fins with a 217-foot wingspan that opens and closes twice a day.[17] At the same time landscape architect Dan Kiley designed the Cudahy Gardens.[18] A $34 million renovation to the War Memorial section of the museum was completed in 2015, with a major reimagining of the lakefront entrance and a reorganization and expansion of the gallery space.[19] Early in 2016, the Museum agreed to purchase the lower levels of the War Memorial, as well as O’Donnell Park and the adjacent parking structure, from Milwaukee County.[20]

Footnotes [+]

- ^ “Museum Info,” Milwaukee Art Museum, accessed November 12, 2014.

- ^ “Collections,” Milwaukee Art Museum, accessed November 9, 2014.

- ^ Lillian B. Miller, “The Milwaukee Art Museum’s Founding Father: Frederick Layton (1827-1919) and His Collection,” in 1888: Frederick Layton and His World, ed. Robert M. Tilendis (Milwaukee: Milwaukee Art Museum, 1988), 21.

- ^ Miller, “The Milwaukee Art Museum’s Founding Father”, 23.

- ^ Russell Bowman, “An Introduction to the Milwaukee Art Museum—Past and Future,” in Building a Masterpiece: Milwaukee Art Museum, ed. Franz Schulze (New York: Hudson Hills Press, Inc., 2001), 11; “Memorials That Live: Useful War Shrines Urged by Robey Parks,” Milwaukee Sentinel, April 17, 1945.

- ^ Goldstein, Guide to the Permanent Collection, 12.

- ^ Cheryl Kent, Santiago Calatrava: Milwaukee Art Museum Quadracci Pavilion (New York: Rizzoli, 2005), 31.

- ^ Bowman, “An Introduction to the Milwaukee Art Museum,” 11.

- ^ Goldstein, Guide to the Permanent Collection, 13.

- ^ Kent, Santiago Calatrava, 31.

- ^ Kent, Santiago Calatrava, 31.

- ^ Goldstein, Guide to the Permanent Collection, 13.

- ^ “Quadracci Pavilion,” Milwaukee Art Museum, accessed November 8, 2014.

- ^ Kent, Santiago Calatrava, 55.

- ^ Kent, Santiago Calatrava, 31.

- ^ “Quadracci Pavilion,” Milwaukee Art Museum,accessed November 8, 2014.

- ^ “Cudahy Gardens,” Milwaukee Art Museum, accessed November 9, 2014.

- ^ “Uncrated. Unveiled,” Milwaukee Art Museum, last accessed June 6, 2017.

- ^ “Art Museum to Acquire O’Donnell Park in Deal Valued at $28.8 Million,” Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, March 8, 2016, last accessed June 6, 2017.

For Further Reading

Eastberg, John C., and Eric Vogel. Layton’s Legacy: A Historic American Art Collection, 1888-2013. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 2013.

Goldstein, Rosalie, ed. Guide to the Permanent Collection. Milwaukee: Milwaukee Art Museum, 1986.

Kent, Cheryl. Santiago Calatrava: Milwaukee Art Museum Quadracci Pavilion. New York: Rizzoli, 2005.

Schulze, Franz. Building a Masterpiece: Milwaukee Art Museum. New York: Hudson Hills Press, Inc., 2001.

Tilendis, Robert M., ed. 1888: Frederick Layton and His World. Milwaukee: Milwaukee Art Museum, 1988.

0 Comments

Please keep your community civil. All comments must follow the Encyclopedia of Milwaukee Community rules and terms of use, and will be moderated prior to posting. Encyclopedia of Milwaukee reserves the right to use the comments we receive, in whole or in part, and to use the commenter's name and location, in any medium. See also the Copyright, Privacy, and Terms & Conditions.

Have a suggestion for a new topic? Please use the Site Contact Form.