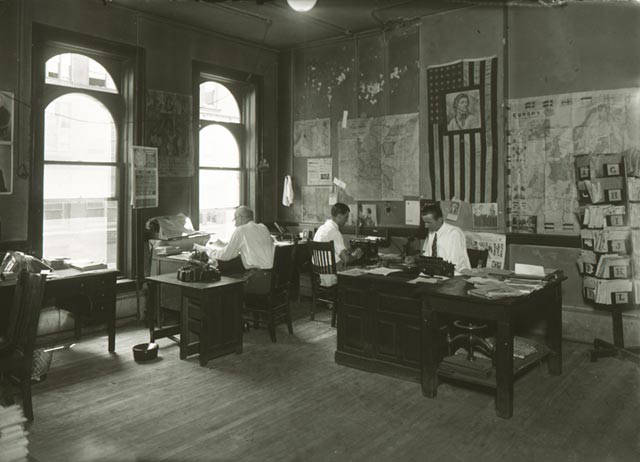

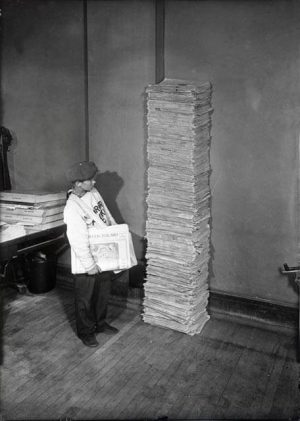

By the mid-1880s, Milwaukee’s mushrooming Polish language speaking immigrant population was estimated at 30,000 in a city of 200,000.[1] Recognizing the possibilities of a newspaper for its members, the twenty-five year old Michael Kruszka, along with several aspiring, headstrong, and radical colleagues, founded a series of publications. The first in 1885 was a tiny publication, Tygodnik Anonsowy (Weekly Announcement), followed soon after by Krytyka (The Critic), and Dziennik Polski (The Polish Daily); all failed, with Kruszka losing every cent. Borrowing $125, he made a fourth try with the Kuryer Polski. The paper’s first edition appeared on June 28, 1888, with Kruszka serving as publisher, editor, bill collector, and typesetter. This time he succeeded. From about 300 readers in 1888, the Kuryer claimed a daily circulation of 3,000 by 1891 and 18,000 in 1905—several hundred in Chicago alone. Starting with six employees, by 1905 the Kuryer’s payroll counted 121 office personnel and delivery boys. By then, its office in a downtown building on Milwaukee and Michigan streets, the Kuryer Polski publishing firm, its net worth about $1 million, was also putting out other periodicals and a wide variety of books in popular fiction and history. That year, its most notable early rival, the Dziennik Milwaucki, established in 1895, went bankrupt.[2]

Reducing the paper’s annual subscription price from $5 to $3 was one explanation for its growth. More important, Kruszka effectively focused his readers’ attention on the political issues of the day. His newspaper called on them to become citizens and to vote for candidates of Polish origin and non-Poles friendly to their interests. The Kuryer appealed for ethnic solidarity in frequenting Polish-owned businesses and strongly advocated for workers’ rights. Already in 1890 Kruszka’s views and political skills won him an election victory to the Wisconsin state assembly; two years later he became the first Pole in the United States to win a state senate seat. While in office he backed workers’ rights and also won approval for all official government notices, which were already published in English and German, to be printed in Polish as well and by his company.[3]

Ambitiously proclaiming the Kuryer Polski, the “organ of the Polish people in America,” Kruszka won readers across the country. Editorially, the newspaper’s nationalist perspective coincided with events in the Polish lands ruled by imperial Germany, which had combined with imperial Russia and Austria to destroy the once independent Polish state a century before. There, resentment was rising against Berlin’s ruthless assimilationist policies, a matter the Kuryer covered extensively and which particularly resonated with his Wisconsin readers, who hailed overwhelmingly from German-ruled provinces.[4] Kruszka also championed elevating worthy priests of Polish origin to bishop in the Catholic Church in America and publicized the writings and activities of his half-brother, the Rev. Wenceslaus (Waclaw) Kruszka.[5]

The Kuryer Polski also engaged in controversy. Kruszka called for the public schools in Milwaukee’s Polish neighborhoods to teach in the Polish language, as German was taught in the public schools in the city’s German neighborhoods. But this position put him at odds with Polish clergymen who viewed this position as an attack on their parish schools. The Kuryer’s criticism of Archbishop Sebastian Messmer for his alleged failure to deal with the financial crisis afflicting the newly built St. Josaphat church led Messmer to call on Polish clergymen to underwrite an opposition Catholic paper, Nowiny Polskie (Polish News) in 1907. Its first editor was the Rev. Boleslaw Goral.[6]

In 1911, Kruszka and the Kuryer played a key role in creating the militant Federation of Polish Catholic Laymen, an organization sharply critical of Archbishop Messmer, and which later became the Federation Life Insurance of America.[7] Messmer, in concert with his fellow Wisconsin bishops, reacted by forbidding Polish Catholics to read the Kuryer. Kruszka sued the bishops for $100,000 ($2 million today) but the Wisconsin Supreme Court ruled against him in 1916.[8] In the meantime the newspaper’s readership, which was also giving enormous coverage to partitioned Poland’s World War I independence (proclaimed in Warsaw on November 11, 1918), rose to 40,000.[9] Just three weeks later Kruszka died suddenly.

In later years, the Kuryer Polski, under a series of editors, most notably, Chester Dziadulewicz (1918-1938), remained Milwaukee’s most widely read Polish language daily.[10] In 1948, its rival, the Nowiny Polskie, went out of business.[11] But before that occurred, two of its editors, Thaddeus Borun and John J. Gostomski, published We, the Milwaukee Poles (1946), an invaluable volume celebrating the Polish contribution to the city on the 100th anniversary of its incorporation.[12]

Politically, the Nowiny Polskie aligned with the Democratic Party. The more independent Kuryer Polski supported the Progressive Republican cause in the era of Senator “Fighting Bob” La Follette and his sons. From 1910, a time when the Socialist party became a serious force among many Milwaukee Poles, a weekly Polish socialist paper, Naprzod (Forward), operated briefly.[13]

In 1962 the Kuryer Polski, by then a weekly whose pages included substantial English-language material, went out of business. Its failure was mainly a consequence of the end of substantial Polish immigration to Milwaukee decades before and the fact that relatively few Poles settled in Milwaukee after World War II. By the time the paper closed shop its audience had largely disappeared. The 74 year old Kuryer Polski was then the oldest privately-owned Polish language paper in continuous operation in the United States.[14]

In the English language press, the work of at least two Americans of Polish heritage has won attention. One was Edward Kerstein, a Milwaukee Journal reporter. Kerstein published two significant books, one a biography of Milwaukee Mayor Daniel Webster Hoan, the second an eye-witness account of post-World War II Poland.[15] (Before retiring in the 1970s he published his observations in visiting Poland again.[16]) More recently, Milwaukee historian John Gurda has authored a monthly Sunday column in the Milwaukee Journal-Sentinel, occasionally featuring stories connected with the city’s Polish community. (In the 1970s and early 1980s, the Milwaukee Journal ran a weekly column focused on the city’s ethnic groups. In it Polish Americans received considerable coverage.)

In other mass communication fields, e.g., radio, the Polish presence was notable. From the 1930s into the 1960s, variety programs were hosted by Anthony Szymczak and Captain Stanley Nastal.[17] Following their retirements, Polish-language radio programs continued into the 1980s, hosted most notably by Maria Komornicka, a post-World War II émigré with decided patriotic views. Polka shows also abounded, most recently into the 2000s, one hosted by Jerry Halkoski.[18] In television, several personalities of Polish ancestry were visible, notably August “Gus” Gnorski and TV newscaster Joyce Garbaciak.

Footnotes [+]

- ^ Waclaw Kruszka, A History of the Poles in America to 1908, vol. I (Washington: D.C.: The Catholic University Press of America, 1993), 280.

- ^ Kruszka, A History of the Poles in America to 1908, 282, 290, 296-298; James S. Pula, ed.,The Polish American Encyclopedia (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2011), s.v. “Michael Kruszka,” 249.

- ^ Pula, The Polish American Encyclopedia, s.v. “Michael Kruszka” and “Kuryer Polski,” 249, 259; J.A. Kapmarski, “The Kuryer Polski,” in We, the Milwaukee Poles, edited by Thaddeus Borun (Milwaukee: Nowiny Publishing, 1946), 53-56.

- ^ Piotr S. Wandycz, The Lands of Partitioned Poland, 1795-1918 (Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press, 1974), 228-238, 281-288, 319-323.

- ^ Pula, The Polish American Encyclopedia, s.v. “Michael Kruszka” and “Waclaw Kruszka,” 249-251; Donald Pienkos, “Politics, Religion, and Change in Polish Milwaukee, 1900-1930,” Wisconsin Magazine of History 61, no. 3 (Spring 1978), 196-203.

- ^ Pienkos, “Politics, Religion, and Change in Polish Milwaukee, 1900-1930,” 197, 200; Pula, The Polish American Encyclopedia, s.v. “Nowiny Polskie,” 331; Anthony J. Kuzniewski, Faith and Fatherland: The Polish Church War in Wisconsin, 1896-1918 (Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press, 1980), 65-67.

- ^ Angela T. Pienkos, A Brief History of Federation Life Insurance of America, 1913-1976 (Milwaukee: Haertlein Graphics, 1976), 2-4.

- ^ Pula, The Polish American Encyclopedia, s.v. “Michael Kruszka,” 249.

- ^ Pienkos, “Politics, Religion, and Change in Polish Milwaukee, 1900-1930,” 197.

- ^ Pienkos, “Politics, Religion, and Change in Polish Milwaukee, 1900-1930,” 197.

- ^ Pula, The Polish American Encyclopedia, s.v. “Nowiny Polski,” 331.

- ^ Thaddeus Borun and Casimir Pulaski Council of Milwaukee, We, the Milwaukee Poles: The History of Milwaukeeans of Polish Descent and a Record of Their Contributions to the Greatness of Milwaukee (Milwaukee: Nowiny Pub. Co., 1946).

- ^ Pienkos, “Politics, Religion, and Change in Polish Milwaukee, 1900-1930,” 186, 190, 196-197.

- ^ Pula, The Polish American Encyclopedia, s.v. “Kuryer Polski,” 259; “Kuryer Polski Records, 1907-1961,” University of Wisconsin Digital Collections finding aid, last accessed July 5, 2017.

- ^ Edmund Olszyk, “Milwaukee’s Polish Journalists,” in We, the Milwaukee Poles, edited by Thaddeus Borun (Milwaukee: Nowiny Publishing, 1946), 117-119. Edward S. Kerstein, Milwaukee’s All-American Mayor; Portrait of Daniel Webster Hoan (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1966); Edward S. Kerstein, Red Star over Poland, a Report from behind the Iron Curtain (Appleton, WI: C. C. Nelson, 1947).

- ^ Edward S. Kerstein, Panorama, Poland: A Series of Articles Based on 5,000 Mile, Thirty Day Traverse of Poland (Milwaukee: Milwaukee Journal, 1971).

- ^ “Stanley I. Nastal Papers, 1922, 1934-1954,” University of Wisconsin Digital Collections finding aid, last accessed July 5, 2017; Tim Cuprisin, “Milwaukee’s Polonia: At the Crossroads,” The Milwaukee Journal, December 27, 1993, B3.

- ^ Polka Parade website, last accessed July 5, 2017.

For Further Reading

Kapmarski, J.A. “The Kuryer Polski.” In We, the Milwaukee Poles, edited by Thaddeus Borun, 53-56. Milwaukee: Nowiny Publishing, 1946.

Kruszka, Waclaw. A History of the Poles in America to 1908, Part I. Washington D.C.: The Catholic University of America Press, 1993.

Kuzniewski, Anthony J. Faith and Fatherland: The Polish Church War in Wisconsin, 1896-1918. Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press, 1980.

Olszyk, Edmund. “Milwaukee’s Polish Journalists.” In We, the Milwaukee Poles, edited by Thaddeus Borun, 117-119. Milwaukee: Nowiny Publishing, 1946.

Pienkos, Angela T. A Brief History of Federation Life Insurance of America, 1913-1976. Milwaukee: Haertlein Graphics, 1976.

Pienkos, Donald. “Politics, Religion, and Change in Polish Milwaukee, 1900-1930.” Wisconsin Magazine of History 61, no. 3 (Spring 1978): 179-209.

Pula, James S., ed. The Polish American Encyclopedia. Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2011.

Wandycz, Piotr S. The Lands of Partitioned Poland, 1795-1918. Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press, 1974.

0 Comments

Please keep your community civil. All comments must follow the Encyclopedia of Milwaukee Community rules and terms of use, and will be moderated prior to posting. Encyclopedia of Milwaukee reserves the right to use the comments we receive, in whole or in part, and to use the commenter's name and location, in any medium. See also the Copyright, Privacy, and Terms & Conditions.

Have a suggestion for a new topic? Please use the Site Contact Form.