Milwaukee has been an important baseball location in professional baseball since the 1870s. It has never been the hub of mid-western baseball and certainly never could be with Chicago’s close proximity. The last quarter of the nineteenth century and first half of the twentieth century often found Milwaukee in the thick of major league baseball but never able to support a major league team in the long-term. But because Chicago, a city with two major league teams for most of its history, would not support a minor league team, Milwaukee became the “big city” for many high level minor league teams. In 1953 the world finally realized Milwaukee could be a major league city, having paid its dues for almost a century.

The Early Days

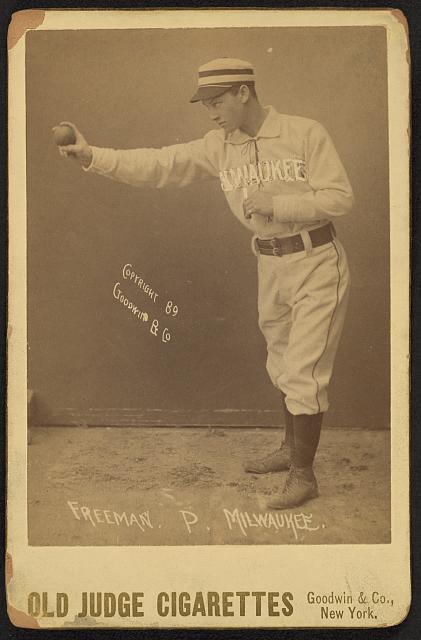

Professional baseball teams made appearances in Milwaukee beginning in 1868. A year later, the famous Cincinnati Red Stockings routed a local amateur team 85 to 7.[1] However, the first all-professional baseball team to form in Milwaukee was the West End Club in 1877.[2] After playing one season in a loosely formed association, the owners decided to join the recently created National League in 1878.[3] The Grays finished in last place with a 15 and 45 record.[4] The one bright spot was outfielder Abner Dalrymple, whose .354 batting average earned him the batting title.[5] After a single season the club was expelled from the National League.[6] In 1884 Milwaukee fielded a team in the Northwestern League. When the league experienced financial trouble, the club joined the newly formed major league Union Association, finishing with an 8 and 4 record.[7] This league lasted only one season. Milwaukee fielded teams in one minor league or another from 1885 until 1890, but found little success on the field. Perhaps the most famous player to appear in a Milwaukee uniform in these years was Clark Griffith, a young pitcher who would go on to win 237 big league games, serve as the first manager of the New York Yankees, and later own the Washington Senators.[8] In 1891 Milwaukee again became a major league city when the minor league Brewers finished the season for the defunct Cincinnati franchise of the American Association. The Brewers—this nickname, first used by the Milwaukee Sentinel on August 4, 1888, but now firmly attached to the team—finished the season with a 21 and 15 record.[9] The league dropped Milwaukee shortly after the season.[10] Beginning in 1894 Milwaukee fielded a team in the newly formed Western League. The legendary Connie Mack managed it from 1897 to 1900.[11]

The major highlight of this period was owner James A. Hart’s building of Athletic Park at 8th and Chambers in 1888, where teams played until 1894.[12] This ballpark again came into use in 1902 and for the next half-century would be the home of the American Association Brewers. It was renamed Borchert Field in 1928.[13] Another ballpark at 16th and Lloyd Street hosted professional baseball teams from 1895 through the 1903 season.[14]

The Western League was renamed the American League in 1900, and the next year claimed major league status, beginning a trade war with the National League. Future Hall of Famer Hugh Duffy managed the team to a miserable 48-89 record.[15] Drawing only 139,034 spectators,[16] the club was a financial failure, and after a single season the team moved to St. Louis, re-named the Browns, and after yet another move eventually became today’s Baltimore Orioles.

Minor League Brewers

Milwaukee had two minor league teams in 1902 and 1903, the Brewers in the American Association and the Creams in the Western League. Hugh Duffy managed the Creams to the Western League pennant in 1903.[17] The Western League transferred the Creams after the 1903 season, but the Brewers played for another fifty seasons. The Brewers, playing at the park at 8th and Chambers, were owned by ex-alderman Charles Havenor until his death in April 1912.[18] After his death, his wife, Agnes, took over the presidency of Brewers, and the 1913 squad won the American Association championship, repeating the feat in 1914.[19] One player of note on these teams was a Milwaukee boy, Oscar “Happy” Felsch, who was involved in the infamous “Black Sox” scandal at the 1919 World Series.[20] After these two championship seasons, the club fell on hard times. While the Brewers were not much on the field in the later part of this decade, one superstar played in Milwaukee. In 1916 Jim Thorpe—the greatest athlete in the word—roamed the outfield at 8th and Chambers.[21]

Local businessman Otto Borchert, a self-made millionaire, headed a group that purchased the Brewers in 1920, soon buying out all the other investors.[22] Borchert made large profits from the baseball club by finding, developing, and then selling talent to the major leagues. The best known was local lad and future Hall of Famer Al Simmons, whom he sold to the Philadelphia Athletics for three players and $40,000.[23] After Borchert died of a heart attack in 1927 while addressing the downtown Elks Club the night before opening day,[24] the Brewers had a series of short-lived owners, including two women, an unusual occurrence for the times. The team found glory on the field only in 1937, winning the minor league championship, known as the Little World Series.[25] Some historians consider this Brewer team one of the best teams in minor league history.[26]

A syndicate headed by Bill Veeck—who would later take his entrepreneurial showmanship to the big leagues—purchased the Brewers in June 1941.[27] Veeck took a hands-on approach to the team, greeting fans at the park, making improvements to the ballpark, and spending more money on players. He put on a number of special nights and days for fans, including presenting a trophy to himself for the biggest opening day crowd of 1942, scheduling morning games with free breakfasts for workers getting off night shifts, and a “vaudeville night” with players proving the entertainment.[28] When his manager, Charley Grimm, needed another pitcher for the 1943 pennant race, Veeck arranged on the manager’s birthday for a group of dancing girls to break out of a giant cardboard cake on the field, followed by newly acquired left handed pitcher.[29] The Brewers won the American Association pennant in 1943.[30] Casey Stengel, who later won ten American League pennants and seven World Series for the New York Yankees, succeeded Charley Grimm.[31] During his one season with the club Stengel led the Brewers to 102 wins and another championship.[32] After the 1945 season Veeck sold the Brewers, and in 1946 Boston Braves’ owner Lou Perini purchased the club.[33] As a Braves’ farm club, the Brewers brought Little World Series titles to Milwaukee in 1946 and 1951.[34] The Brewers put another pennant in the books in 1952.[35]

Other Teams of Note

In 1913 Milwaukee had a second minor league team. The Mollys—named after owner Charles Moll—that played in the Wisconsin-Illinois League, a lower classified league, and consisted mainly of younger players. The team did not draw well, and in June was transferred, with its 29-20 record, to Fond du Lac.[36]

While the Brewers remained the main attraction in Milwaukee, the Negro National League put a team in Milwaukee in 1923. Managed by future Hall of Famer Pete Hill, the Bears compiled a 15-51-1 record in their only season.[37]

Philip Wrigley, owner of the Chicago Cubs, started the All-American Girls Professional Ball League in 1943, with teams in Rockford, Kenosha, Racine, and South Bend. For 1944 Milwaukee and Minneapolis were added to the league. In its only season in the league the “Chicks” finished with the best overall record, 70-45. Having won the second half of the split season, the Chicks beat the first half winners, the Kenosha Comets, in the championship playoff series, four games to three.[38]

National League Braves

The 1952 season was the last for the American Association Brewers, as Lou Perini moved his Boston Braves to play in newly built Milwaukee County Stadium in March 1953.[39] In their first season the Braves drew 1,826,397 fans, a National League season record (the Braves led the National League in attendance from 1953 to 1958).[40] Third baseman Eddie Mathews led the National League with 47 home runs, and veteran left hander Warren Spahn led the league with 23 wins.[41] In spring training of 1954 outfielder Bobby Thomson broke his ankle and a young unproven player named Henry Aaron took over in left field.[42]

Milwaukee fans immediately began a love affair with the team, showering the players with a variety of gifts, from food to furniture.[43] A Milwaukee tradition is associated with these Braves’ teams, although it started in 1948 with the minor league Brewers. George Webb, owner of a local restaurant chain posted predictions that the Braves would win 12 straight games. In the event his prediction came true, Webb restaurants would give out free hamburgers.[44] The closest Webb came to making good on his offer was in 1956 when the Braves won 11 consecutive games in June.[45]

After second place finishes in 1955 and 1956, the Braves won the National League pennant in 1957.[46] Pitcher Lew Burdette dominated the New York Yankees in the World Series, to give Milwaukee the World Championship.[47] The Braves repeated as National League champs in 1958, but lost the World Series to the Yankees in seven games.[48] 1959 saw the Braves tied with the Los Angeles Dodgers at the end of the season with 86 and 68 records.[49] In the league play-off series the Dodgers won the right to go to World Series.[50]

One of the reasons for the Braves’ success during these years was the pitching of Warren Spahn, who, despite turning 36 in 1957, led the league in games won from 1957 to 1961, recording more than 20 victories each season. He continued pitching great baseball, winning 23 games for the Braves in 1963 at the age of 42.[51] These great Braves’ teams had four of its core players—Henry Aaron, Eddie Mathews, Warren Spahn, and Red Schoendienst—elected to baseball’s Hall of Fame.

The Braves continued playing over .500 baseball for the next six years, but did not win another National League pennant. Attendance was respectable in 1960 and 1961, but there was a huge drop in 1962.[52] This was partially due to the County Board’s decision in April to stop fans from bringing their own beer into the stadium.[53] On November 16, 1962, Lou Perini sold the Braves to a syndicate of six Chicago businessmen and Braves president John J. McHale for $5,500,000.[54] In October 1964, the Braves ownership requested permission to move the ball club to Atlanta,[55] but an injunction forced the team to remain in Milwaukee one more season.[56] The lame duck team recorded a season home attendance of only 555,584.[57] The Braves opened the 1966 season in Atlanta.[58]

With no team in Milwaukee, the Chicago White Sox played nine home games at Milwaukee County Stadium in 1968, drawing a total attendance of 264,478. In 1969 the White Sox played 11 home games in Milwaukee, drawing considerably fewer fans.[59]

Major League Brewers

On March 17, 1970 the American League approved the move of the bankrupt Seattle Pilots to Milwaukee, but a court injunction temporarily prevented this.[60] After a brief delay, a federal bankruptcy judge approved the $10.8 million offer for the Pilots by the Milwaukee syndicate headed by Bud Selig.[61] An opening day crowd of 36,107 at Milwaukee County Stadium witnessed what would be the fate of most early Brewer teams, a 12-0 loss to the California Angels.[62] Brewers fans suffered through eight losing seasons before the 1978 squad posted a 93-69 record, good for third place.[63] This team, known as Bambi’s Bombers after manager George Bamberger,[64] finished in second and third place the next two seasons before taking first place in the second half of a strike shortened season in 1981. They lost to the Yankees in a five game Division Series playoff.[65] The 1982 Brewers came to be known as Harvey’s Wallbangers[66] (after Harvey Kuenn, who took over as manager on June 2[67]) as they hit a major league high 216 home runs in the regular season and won ninety-five games on the way to winning the American League Eastern Division championship. The team lost the World Series to the St. Louis Cardinals in seven games.[68] Three mainstays of this team were later enshrined in baseball’s Hall of Fame: Robin Yount, Paul Molitor, and Rollie Fingers.

Over the next fifteen years, the Brewers fielded mostly mediocre teams, finishing as high as second place only once. Perhaps the highlight of the dismal period was the thirty-nine game hitting streak of Paul Molitor in 1987, seventh longest in major league history.[69] In this same year, on April 19, the Brewers won their twelfth straight game (they would win thirteen straight), and George Webb restaurants gave away 168,194 free hamburgers.[70] Fay Vincent resigned as the commissioner of baseball on September 7, 1992, and Bud Selig was appointed acting commissioner two days later.[71] That same night Brewer center fielder Robin Yount collected his 3,000th hit.[72] On July 9, 1998, the baseball owners unanimously elected Selig the ninth commissioner of baseball.[73] One month later, Selig’s daughter, 38-year old Wendy Selig-Prieb, took over as president and CEO of the Brewers.[74] This was the fourth time in the twentieth century a woman headed the top baseball team in Milwaukee.

In 1998 the team switched to the Central Division of the National League,[75] but continued its losing ways, managing a .500 record only once in the next nine seasons. On April 6, 2001, the Brewers’ new state of the art home, Miller Park, hosted its first game before 42,024 fans, with Bud Selig and President George W. Bush throwing ceremonial first pitches. The Brewers beat the Cincinnati Reds, 5-4.[76] Wendy Selig-Prieb stepped down as the club president in September 2002 and was replaced by Ulice Payne Jr., the first African American to be a president of a major league team.[77] Payne left as president on November 20, 2003, in a dispute with the board of directors over payroll cuts.[78] In January 2005 Los Angles investor Mark Attanasio, head of a group that purchased the Brewers from the Selig family for $223 million, formally took over as president of the Brewers.[79] With a cohort of strong, talented players, headed by Prince Fielder and Ryan Braun, the 2007 Brewers managed a second place finish. This same young core, plus a sensational second half by mid-season pickup CC Sabathia, put the 2008 Brewers in the National League Division Championship Series. However, in the first post-season appearance for a Milwaukee team since 1982, the Brewers lost to the Philadelphia Phillies, 3 games to 1.[80] In 2011 the Brewers took first place in the National League central division, but lost to the St. Louis Cardinals in the National League Championship series.[81] They have not reached the playoffs since.

Footnotes [+]

- ^ “The National Game,” Milwaukee Daily Sentinel, July 31, 1869.

- ^ “The Milwaukee Baseball Club,” Milwaukee Sentinel, March 13, 1877.

- ^ Dennis Pajot, The Rise of Milwaukee Baseball (McFarland Publishers, North Carolina, 2009), 48.

- ^ “1878 Milwaukee Grays,” baseball-reference.com, last accessed March 1, 2017.

- ^ “Abner Dalrymple,” baseball-reference.com, accessed March 1, 2017.

- ^ Meeting of the Board of Directors of the National League of Professional Base Ball Clubs, Dec. 3, 1878, last accessed March 10, 2017.

- ^ “The New Ball Club,” Milwaukee Sentinel, January 12, 1884; “Milwaukee Brewers Franchise (1884),” baseball-reference.com, last accessed March 1, 2017.

- ^ “Clark Griffith,” baseball-reference.com, last accessed March 1, 2017.

- ^ “Milwaukee Gets It,” Milwaukee Journal, August 18, 1891; “1891 Milwaukee Brewers,” baseball-reference.com, last accessed March 1, 2017.

- ^ “The Consolidation,” The Sporting Life 18 no.13 (December 26, 1891): 4.

- ^ Doug Skipper, “Connie Mack,” SABR Baseball Biography Project, accessed March 1, 2017.

- ^ “The Site Chosen,” Milwaukee Sentinel, February 15, 1888.

- ^ George F. Downer, “Killilea Now Sole Owner of Brewers,” Milwaukee Sentinel, January 4, 1928.

- ^ “Leases Another Park,” Milwaukee Sentinel, February 27, 1895.

- ^ “1901 Milwaukee Brewers Statistics,” baseball-reference.com, last accessed March 1, 2017.

- ^ “Close to 4,000,000—Major League Patronage of Last Season,” The Sporting News 31, no.6 (October 19, 1901): 6.

- ^ Reach’s Official American League Base Ball Guide for 1904 (Philadelphia: A.J. Reach, 1903), 229.

- ^ “Charles S. Havenor, Brewer Owner Dies,” Milwaukee Sentinel, April 4, 1912.

- ^ Brownie [W.W. Rowland], “Strength of the Various Teams in A.A. Circuit Still Unknown, Milwaukee Journal, April 4, 1912; Manning Vaughan, “Milwaukee Brewer A.A. Champs,” Milwaukee Sentinel, September 29, 1913.

- ^ “Happy Felsch,” baseball-reference.com, last accessed March 1, 2017.

- ^ “Jim Thorpe, Noted Indian Athlete, To Wear Brewer Uniform,” Milwaukee Journal, April 2, 1916.

- ^ Manning Vaughan, “O’Brien and Borchert Purchase Brewers,” Milwaukee Evening Sentinel, January 12, 1920.

- ^ “Otto Borchert, Games’ Greatest Salesman,” Milwaukee Journal, April 28, 1927; “Al Simmons,” baseball-reference.com, last accessed March 1, 2017.

- ^ “Otto Borchert Dies Speaking at Banquet,” Milwaukee Sentinel, April 28, 1927.

- ^ Red Thisted, “Brewers Beat Buffalo, 8-3, To Win Crown,” Milwaukee Sentinel, October 2, 1936.

- ^ Rex Hamann and Bob Koehler, The American Association Milwaukee Brewers (Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing 2004), 83.

- ^ Sam Levy, “Brewers Sold for $100,000; Charley Grimm Named Manager,” Milwaukee Journal, June 23, 1941.

- ^ Arthur Bystrom, “Free Breakfasts, Vaudeville, Swing Bands Draw Milwaukee Baseball Fans,” Ludington Daily News, July 14, 1943.

- ^ “New Pitcher Steps from Birthday Cake as Veeck’s Gift to Grimm,” Milwaukee Journal, August 29, 1943.

- ^ Sam Levy, “Two Victories Give Brews Eight in Row,” Milwaukee Journal, September 20, 1943.

- ^ “Casey Takes Over Sunday,” Milwaukee Sentinel, May 7, 1944.

- ^ Sam Levy, “Brewers Close Season with a Double Victory,” Milwaukee Journal, September 11, 1944; R. G. Lynch, “Stengel Announces He Won’t Be Back,” Milwaukee Journal, September 22, 1944.

- ^ “Braves Take Over Brews—Officially,” Milwaukee Sentinel, October 25, 1946.

- ^ Red Thisted, “Game Brews Rally to Win Series,” Milwaukee Sentinel, October 5, 1951.

- ^ Red Thisted, “Brews Win Two; Liddle in 1-Hitter,” Milwaukee Sentinel, September 7, 1952.

- ^ “Fondy Gets Schnitts,” Milwaukee Journal, June 26, 1913.

- ^ “Milwaukee Bears,” baseball-reference.com, last accessed March 1, 2017.

- ^ Thomas J. Morgan and James R. Nitz, “Our Forgotten World Champions: The 1944 Milwaukee Chicks,” in Baseball in the Badger State (Cleveland, OH: Society for American Baseball Research, 2001), 26-32.

- ^ Lloyd Larson, “Big League Ball Here This Year!,” Milwaukee Sentinel, March 14, 1953.

- ^ Attendance, County Stadium, Milwaukee, Milwaukee Braves.info, accessed March 1, 2017.

- ^ “Eddie Mathews,” baseball-reference.com, last accessed March 1, 2017; “Warren Spahn,” baseball-reference.com, last accessed March 1, 2017.

- ^ Bob Wolf, “Bench Saves Braves; Loss of Thomson May Be Break for Aaron,” Milwaukee Journal, March 17, 1954.

- ^ “Sausages, Sauerbraten and Sympathy: Rousing Support by Milwaukee Fans Brings Braves Shower of Gifts and Lifts Them to Top of League,” Life Magazine 35, no. 1, (July 6, 1953): 39-42.

- ^ “George Webb Predicts…,” Milwaukee Braves.info, last accessed March 1, 2017.

- ^ “A Brave Gesture by Webb, 10,000 Hamburgers for 12,” Milwaukee Journal, June 26, 1956.

- ^ Doyle K. Getter, “Braves Win Flag: It’s Bedlam!” Milwaukee Journal, September 24, 1957.

- ^ Bob Wolf, “Oct. 10 Is Day to Remember; Burdette Feat Unforgettable,” Milwaukee Journal, October 11, 1957.

- ^ Red Thisted, “No Joy in Bushville!: Yankees Beat Burdette, 6-2, to Regain Crown,” Milwaukee Sentinel, October 10, 1958.

- ^ Red Thisted, “Braves Tie for Title,” Milwaukee Sentinel, September 28, 1959.

- ^ Red Thisted, “There’s Always 1960; Comeback L.A. Champ!,” Milwaukee Sentinel, September 30, 1959.

- ^ “Warren Spahn,” baseball-reference.com, last accessed March 1, 2017.

- ^ Attendance, County Stadium, Milwaukee, Milwaukee Braves.info, accessed March 1, 2017.

- ^ “Well, That’s Settled!,” Milwaukee Journal, April 18, 1962.

- ^ Red Thisted, “McHale, Six Others Buy Braves for $5.5 Million,” Milwaukee Sentinel, November 17, 1962.

- ^ “Braves’ Directors Request Transfer to Club to Atlanta,” Milwaukee Journal, October 21, 1964.

- ^ “League Orders Braves to Stay Here,” Milwaukee Journal, November 7, 1964.

- ^ Attendance, County Stadium, Milwaukee, Milwaukee Braves.info, accessed March 1, 2017.

- ^ Red Thisted, “Braves Atlanta Debut a 3-2 Flop,” Milwaukee Sentinel, April 13, 1966.

- ^ Frank Jackson, “A Short History of the Milwaukee White Sox,” The Hardball Times, March 27, 2013, last accessed March 1, 2017.

- ^ “Injunction Bars Pilots’ Move Here: A.L. Fights Seattle Suit,” Milwaukee Sentinel, March 18, 1970.

- ^ “Referee OK’s Pilots Sale, Baseball to Return Here,” Milwaukee Sentinel, April 1, 1970.

- ^ Cleon Walfoort, “Angels Tread on Brewers,” Milwaukee Journal, April 8, 1970.

- ^ Hank Masler, “Brewers’ Best Season Is Vote for Bamberger,” Milwaukee Sentinel, October 2, 1978.

- ^ Don Walker, “No Tags on 2007 Brewers: Baseball’s Long History Laced with Nicknames,” Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, May 18, 2007.

- ^ Don Kausler, Jr., “Brewers’ Big Effort Falls Short,” Milwaukee Sentinel, October 12, 1981.

- ^ Don Walker, “No Tags on 2007 Brewers: Baseball’s Long History Laced with Nicknames,” Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, May 18, 2007.

- ^ Vic Feuerherd, “Rodgers Fired; Kuenn at Helm,” Milwaukee Sentinel, June 3, 1982.

- ^ Vic Feuerherd, “Brewer Hopes Die in Finale,” Milwaukee Sentinel, October 21, 1982.

- ^ Tom Flaherty, “The Beat Is Silent…The Streak Is Stopped,” Milwaukee Journal, August 27, 1987; “Hitting Streaks,” MLB.com, last accessed March 1, 2017.

- ^ Tom Haudricourt, “Deer + Sveum = 12,” Milwaukee Sentinel, April 20, 1987; Jeff Cole, “George Webb to Add Restaurant,” Milwaukee Sentinel, August 11, 1990.

- ^ Bob Berghaus, “Selig an Easy Choice, Other Owners Decide,” Milwaukee Journal, September 10, 1992.

- ^ Tom Flaherty, “Single in 7th Inning is a Host into History,” Milwaukee Journal, September 10, 1992.

- ^ Tom Haudricourt, “Selig Takes the Reins,” Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, July 10, 1998.

- ^ Tom Haudricourt, “Selig-Prieb Officially Takes New Role,” Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, August 5, 1998.

- ^ Jerry Crasnick, “N.L. Brewers Are Misty but Undaunted,” The Sporting News, 222, no. 46 (November 17, 1997): 47.

- ^ Miller Park History, MLB.com, last accessed March 1, 2017.

- ^ Don Walker/Drew Olson, “Brewers Shuffle: Attorney, Civic Leader Ulice Payne to Take Over,” Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, September 26, 2002.

- ^ Tom Haudricourt and Don Walker, “Payne Buyout Complete,” Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, November 21, 2003.

- ^ Tom Haudricourt, “Attanasio Takes Charge,” Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, January 14, 2005.

- ^ Gary D’Amato, “ENDGAME: Phillies Uncork Victory as Brewers Glass Empties,” Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, October 6, 2008.

- ^ Tom Haudricourt, “Brewers Season Comes to a Bitter End,” Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, October 17, 2011.

For Further Reading

Buege, Bob. The Milwaukee Braves: A Baseball Eulogy. Madison, WI: Douglas American Sports Publications, 1988.

Hamann, Rex, and Bob Koehler. The American Association Milwaukee Brewers. Charleston, SC: Arcadia, 2004.

Haudricourt, Tom. Where Have You Gone ’82 Brewers? Stevens Point, WI: KCI Sports Pub., 2007.

Hoffmann, Gregg. Down in the Valley: The History of Milwaukee County Stadium, the People, the Promise, the Passion. Milwaukee, Wis.: Milwaukee Brewers Baseball Club, 2000.

Klima, John. Bushville Wins! The Wild Saga of the 1957 Milwaukee Braves and the Screwball, Sluggers and Beer Swiggers Who Canned the New York Yankees and Changed Baseball. New York: Thomas Dunne Books, 2012.

Olson, Don. Bambi’s Bombers: The First Time Around. Milwaukee, WI: NOSLO Publishing, 1985.

Pajot, Dennis. The Rise of Milwaukee Baseball. Jefferson, NC: McFarland Publishers, 2009.

Podoll, Brian. The Minor League Milwaukee Brewers, 1859-1952. Jefferson, NC: McFarland Publishers, 2003.

Povletich, William. Milwaukee Braves: Heroes and Heartbreak. Madison: WI: Wisconsin Historical Society Press, 2009.

0 Comments

Please keep your community civil. All comments must follow the Encyclopedia of Milwaukee Community rules and terms of use, and will be moderated prior to posting. Encyclopedia of Milwaukee reserves the right to use the comments we receive, in whole or in part, and to use the commenter's name and location, in any medium. See also the Copyright, Privacy, and Terms & Conditions.

Have a suggestion for a new topic? Please use the Site Contact Form.