As the Railway Age developed, Milwaukee enthusiastically welcomed the iron horse. Boosters recognized that participation in the emerging national network of railroads could provide local farmers and manufacturers access to wide markets and bring desirable goods and immigrants to the city, bolstering its economic growth. But the city failed to emerge as the railroad mecca that Chicago became by the late 1860s or that St. Louis achieved a decade later. Yet residents of this growing Wisconsin metropolis hoped that railroads would allow their hometown to compete with their urban rivals. Expectations were high when track laying began on the city’s first railroad, the Milwaukee & Mississippi (previously Milwaukee & Waukesha). “Hurrah for the Rail Road!” said the Milwaukee Sentinel of September 13, 1850. “The first rails of the Milwaukee & Mississippi Rail Road were laid down yesterday, and the first Locomotive…is of the largest size and best pattern, weighing some twenty tons.”[1] Progress westward was slow but sure, with track reaching Madison in 1854 and Prairie du Chien three years later. Railroad fever led to another Milwaukee-based road, the La Crosse & Milwaukee. In 1852 it began construction from the north edge of the city’s business district through Horicon, Beaver Dam, and Portage to La Crosse, reaching that Mississippi River town in 1858.

Prior to the Civil War, iron horse enthusiasts in Milwaukee and Wisconsin struggled to build railroads. The city of approximately 45,000 residents loaned more than $1.6 million to local railroad projects by 1860. But hard times triggered by the severe bank panic of 1857, lack of outside (especially foreign) capital, and other factors led to disappointments and business failures. It was Milwaukee banker ALEXANDER MITCHELL who led the restructuring and strengthening of the city’s pioneer railroads. In 1863, he organized the Milwaukee & St. Paul Railway (M&StP), which took over the La Crosse & Milwaukee, and in 1867 the M&StP absorbed the Milwaukee & Prairie du Chien, a company that earlier had succeeded the bankrupt Milwaukee & Mississippi. Mitchell’s network of railroads transformed Milwaukee into a hub for shipment of wheat from Wisconsin, Minnesota, and Iowa on such a scale that it rivaled Chicago.[2]

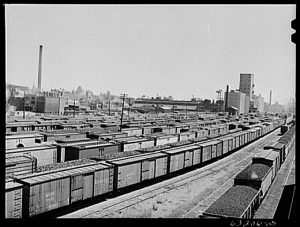

The M&StP expanded rapidly. In 1873 it completed a line between Milwaukee and Chicago, and a year later it became the CHICAGO, MILWAUKEE & ST. PAUL RAILWAY (first called the “St. Paul” and later the “Milwaukee Road”). By 1900 this railroad had become a premier “Granger” carrier with its 6,500 route miles. It claimed to be one of the largest employers in Milwaukee. Although the Milwaukee Road was headquartered in Chicago, Milwaukeeans considered the company their railroad. “Wide-awake” boosters were pleased that by the early twentieth century the railroad assigned top officials of the accounting, operating, and traffic departments to work locally. But more recognizable to the public was the railroad’s massive WEST MILWAUKEE shops complex, established in the late 1870s and modernized over time. Located in the valley of the Menomonee River about three miles west of downtown, the “Shops” became a Milwaukee institution. Here workers maintained and repaired rolling stock and even built steam locomotives and deluxe passenger cars. Generation after generation of area residents were on the Milwaukee Road payroll; many lived within walking distance or a convenient streetcar ride to their assigned work duties.[3]

It would be the CHICAGO & NORTH WESTERN (C&NW) that challenged the Milwaukee Road for domination of Milwaukee’s freight and passenger traffic. Even before the Milwaukee Road reached Chicago, a C&NW affiliate forged a direct connection between Milwaukee and Chicago. By the early twentieth century the C&NW had lines that radiated out of Milwaukee to the north, west, and south, reaching such cities as Ashland, Green Bay, Madison, and Minneapolis-St. Paul. Both systems competed vigorously throughout Wisconsin and the Midwest. Their frequent clashes were aptly described as being that of “two fighting wildcats.”

By the eve of World War I, the Minneapolis, St. Paul & Sault Ste. Marie Railway (universally called the Soo Line) had become a third component of the Milwaukee railroad mix. Its predecessor, the Wisconsin Central Railroad, an important hauler of grain, flour and lumber, reached Milwaukee in the late 1880s by a twenty-seven-mile trackage rights agreement with the Milwaukee Road from its Minneapolis-Chicago main line at Rugby Junction, Wisconsin. But the financially weak Wisconsin Central, leased to the Soo Line in 1909, failed to achieve the importance of either the Milwaukee Road or C&NW in the Milwaukee area. The Wisconsin Central and then the Soo Line were also interested in Lake Michigan ferry connections to Michigan ports and used the Milwaukee Road station for their modest passenger service. Technically two additional steam roads served Milwaukee, Grand Trunk, and Pere Marquette, both providing freight and passenger service by CAR FERRIES. The former operated between Milwaukee docks and those in Muskegon and Grand Haven, Michigan, and the latter connected with Ludington, Michigan.

Railroad-related and support businesses sprang up in Milwaukee, enhancing the city’s role in manufacturing. The Union Refrigerator Transit Company, for example, was headed in the twentieth century by E. L. Philipp, a future governor of Wisconsin. McIntosh Brothers construction company built numerous rail lines, including much of the Milwaukee Road’s Pacific Coast Extension that opened in 1909.

Before the Automobile Age, businesses and manufacturers in Milwaukee relied primarily on its two principal carriers, Milwaukee Road (after 1928 the Chicago, Milwaukee St. Paul & Pacific) and C&NW. These companies carried inbound shipments of coal, grain, lumber and a plethora of additional raw and finished products and outbound shipments of beer, machinery and other goods. Before electric INTERURBANS and motor trucks siphoned off much of less-than-carload (LCL) business, these shipments moved almost exclusively by rail. The Milwaukee Road especially benefitted from the greater number of city businesses and industries, including ALLIS-CHALMERS, Froedtert Malting (later Froedtert Grain and Malting), Hotpoint, Krause Milling, and the BLATZ, MILLER, PABST, and SCHILTZ breweries. Reciprocal switching agreements, however, gave the C&NW some access to these large railroad users.

Milwaukee’s railroads did more than handle carload and LCL freight. Express companies used passenger trains to transport their packages, because prior to 1913 the U.S. Post Office Department delivered only mail. Whether it was American Express or another firm before the federal government forced a restructuring of the express industry during World War I, individuals and companies, large and small, relied on these private express operators. Later the railroad-owned Railway Express Agency (then REA Express) continued the services of the old investor-owned firms until its demise in 1975.[4]

For decades the U.S. mail (until the 1960s) went mostly by rail. One of the first railway post office (RPO) routes in the country began in the mid-1860s between Chicago and Milwaukee. By the 1880s RPO cars were attached to most passenger train movements. For decades the Milwaukee and C&NW also ran solid mail trains to such destinations as Chicago and the Twin Cities. Milwaukeeans could expect overnight delivery of their business and personal letters and postal cards.

Travelers relied heavily on Milwaukee railroads. By the dawn of the twentieth century, the Milwaukee Road and C&NW built depots that were monuments to the Railway Age, offering more than ticket counters, waiting areas, and bathrooms. The companies’ downtown passenger stations were located about a mile apart on Everett Street (Milwaukee Road) and East Wisconsin Avenue (C&NW). They provided a host of services and goods, including purveyors of newspapers, magazines, and oddments. “Red Caps” (often AFRICAN AMERICANS) greeted travelers at the entrance and made certain that their “grips” and trunks went to the correct train. For decades members of the Travelers’ Aid Society helped travelers in need of assistance. During World War II both facilities saw the presence of the United Service Organization (USO). This volunteer group provided complementary travel assistance, food, and lounge facilities, bringing a “touch of home” to thousands of military personnel passing through Milwaukee.

Throughout the day and much of the night, limiteds and locals either originated in or passed through the city’s two bustling passenger stations. By the early twentieth century such trains as the Milwaukee Road’s Pioneer Limited and Chicago-Milwaukee-St. Paul-Minneapolis Special and Milwaukee-Chicago Special and the C&NW’s North Western Limited and Badger State Express had become household names throughout the city. By the turn of the twentieth century these specially named trains featured electric lights, diners, parlor cars, and Pullman sleepers. Then in the mid-1930s, the railroads captured the attention of Milwaukeeans and Midwesterners with introduction of their initially steam-powered streamliners. Travelers flocked to the HIAWATHAS on the Milwaukee Road and the 400’s on the C&NW, which were advertised as “being elegant, fast and dependable.” These trains regularly reached speeds of ninety miles per hour or more, especially on the eighty-five-mile raceway between Milwaukee and Chicago.[5] Dieselization before World War II, which reduced the costs of travel, and new toy train sets for children made these trains even more popular.

Following the crush of traffic during World War II, the Milwaukee Road and C&NW continued to make improvements to their service and equipment. Because of wartime usage, these companies needed to replace their worn out rolling stock. Particularly in need of replacement were hundreds of freight and passenger steam locomotives. The retirement of old equipment encouraged acquisition of diesel-electric motive power to accelerate. The days of “steamers” in and about Milwaukee were numbered; by the mid-1950s they disappeared.

Despite the investment in diesel-electric locomotives, optimism among local railroad officials (and others) about the future of railroading began to fade. The industry’s heyday was over. Competition with other forms of transportation, notably trucking and air transport, ended the dominance of rail in the American transportation network. Shortly after the close of World War II, the Milwaukee Journal made these editorial remarks: “We tax the railroads, but subsidize their competitors. The inconsistency is plain. The result is becoming plain. It will be that railroads cannot make their costs. We shall let them first run down and then go broke.” The editorial concluded: “Either we must subsidize the railroads or require that other forms of transportation—busses and trucks, waterways and especially airways—pay an increasing share of the enormous sums which construction and maintenance are costing the taxpayers.”[6]

The warnings made by the Journal went largely unheeded. By the 1950s modal competition hurt revenues, especially for passenger and LCL operations. Regulation by federal and state authorities, which was largely based on the premise that railroads were transportation monopolies, created worsening financial conditions for the companies. With few reforms coming from Washington and Madison, much of the industry was caught up in the “merger madness” that erupted in the 1960s. Although the Milwaukee Road seriously considered a corporate marriage with rival C&NW, the C&NW became more aggressive (and successful), taking over several competing roads, including the Minneapolis & St. Louis and Chicago Great Western. Still both railroads declined. Some tracks have been abandoned altogether and in the twenty-first century are overgrown with foliage, while others such as the Oak Leaf Trail have been repurposed for recreational BICYCLING.

While the C&NW remained solvent, the Milwaukee Road entered bankruptcy in 1977. It soon shed thousands of miles of track, including much of its transcontinental line to the Pacific Northwest and hundreds of miles of weed-choked and lightly-used appendages. In the early 1980s, with a heavily pared down physical plant and radically reduced workforce, the 3,269-mile Milwaukee Road (“Milwaukee II” as the company called itself) went on the auction block.[7] After considerable corporate maneuvering, the Soo Line took control in 1985.[8] Ten years later, the C&NW also became a “fallen flag,” when Union Pacific acquired ownership.[9] The Soo Line, too, disappeared, joining the sprawling Canadian Pacific Railway system in 1990.

With creation of the National Railroad Passenger Corporation (Amtrak) in May 1971, Milwaukeeans continued to have access to passenger trains. But the level of service was much reduced from what Milwaukee had received as late as 1950, when the Milwaukee Road operated twenty six passenger trains to, from, and through the city, and the C&NW claimed eighteen. Since the 1970s, the Empire Builder has linked Chicago, Milwaukee, Twin Cities, Spokane, and Seattle, and Hiawatha Service has connected Milwaukee with multiple daily runs to and from Chicago and intermediate points. These trains use the Milwaukee Union Station, a modernistic structure located on West St. Paul Avenue that was dedicated on August 3, 1965. Milwaukee became one of the few cities nationally to build a railroad station after the early 1950s. Although the Milwaukee Road was the only occupant of this “union” rail facility, the C&NW soon became a tenant, moving its remaining passenger trains when it closed its lakeside depot. Bus companies, including Greyhound, Wisconsin Coach, and others, also became part of what has emerged as a true intermodal station Reflecting its connection of trains with local and intercity busses, the depot was renamed the Milwaukee Intermodal Station in 2007.[10]

The greater Milwaukee area also includes a small railroad station on South 6th Street near the western edge of General Mitchell International Airport. This convenient facility on the south side of the city, begun in June 2004 and opened the following January, accommodates riders of the Hiawatha Service. Not only was it designed for airline patrons who can ride a shuttle between the station and the passenger terminal, but this facility also serves those who live in the southern portions of the metropolitan area.

The recent story of railroads in Milwaukee also involves freight service. Emerging shortline and regional freight carriers use trackage unwanted by their former owners. This phenomenon became more attractive because of the federal Staggers Act of 1980, a measure that brought about partial rate deregulation and an industry renaissance, and favorable court decisions that involved matters of labor protection. Since 1980, some customers north of Milwaukee have used the services of the Wisconsin & Southern, a start-up railroad that operates on former Milwaukee Road trackage. Then in 1987 Wisconsin Central, Ltd., a new regional railroad, took over much of the Lake States Transportation Division of the Soo Line, property that resembled the pre-1909 Wisconsin Central. It also acquired former Milwaukee Road trackage between Milwaukee and Green Bay. In 2001 the Canadian National Railway purchased this company. Although the industry and maps have changed greatly since the 1960s, railroads remain vital to the Milwaukee community in the twenty-first century.

Footnotes [+]

- ^ “Hurrah for the Rail Road!” Milwaukee Daily Sentinel and Gazette, September 13, 1850.

- ^ John Gurda, The Making of Milwaukee (Milwaukee: Milwaukee County Historical Society, 1999), 100.

- ^ Jim Scribbins, Milwaukee Road Remembered (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2008), 162.

- ^ “REA Inc. Files Bankruptcy,” Lodi News-Sentinel, February 19, 1975, p. 6, last accessed October 13, 2017.

- ^ Jim Scribbins, The Hiawatha Story (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2007), 23; Scribbins, Milwaukee Road Remembered, 69.

- ^ “Railroads Need Fair Play,” The Milwaukee Journal, April 27, 1946, last accessed April 2016.

- ^ August Derleth, The Milwaukee Road: Its First Hundred Years (New York, NY: Creative Age Press, 1948), xxi.

- ^ Scribbins, Milwaukee Road Remembered, 167.

- ^ H. Roger, Grant, The North Western: A History of the Chicago and North Western Railway System (DeKalb, IL: Northern Illinois University Press, 1996), 251.

- ^ “Milwaukee Intermodal Station Sets Grand Opening,” Milwaukee Business Journal, November 23, 2007, last accessed April 2016.

For Further Reading

Derleth, August, The Milwaukee Road: Its First Hundred Years. New York, NY: Creative Age Press, 1948.

Grant, H. Roger, The North Western: A History of the Chicago and North Western Railway System. DeKalb, IL: Northern Illinois University Press, 1996.

Lewis, Edward A. American Shortline Railway Guide, 5th ed. Waukesha, WI: Kalmbach Publishing Company, 1996.

Scribbins, Jim. The 400 Story: Chicago & North Western’s Premier Passenger Trains. Park Forest, IL: PTJ Publishing, 1982.

Scribbins, Jim The Hiawatha Story. Milwaukee, WI: Kalmbach Publishing Company, 1970.

Scribbins, Jim. Milwaukee Road Remembered. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2008.

The Historical Guide to North American Railroads, 3rd ed. Waukesha, WI: Kalmbach Books. 2014.

0 Comments

Please keep your community civil. All comments must follow the Encyclopedia of Milwaukee Community rules and terms of use, and will be moderated prior to posting. Encyclopedia of Milwaukee reserves the right to use the comments we receive, in whole or in part, and to use the commenter's name and location, in any medium. See also the Copyright, Privacy, and Terms & Conditions.

Have a suggestion for a new topic? Please use the Site Contact Form.