The Schlitz Brewing Company (1849-1982) was one of Milwaukee’s industrial brewing giants. Marketed as “the beer that made Milwaukee famous,” Schlitz was an important innovator in the national brewing industry and the largest brewery in the United States for a significant part of the twentieth century.

The Schlitz Brewing Company originated in August Krug’s pioneer restaurant/brewery, established on Chestnut Street (now Juneau), between Fourth and Fifth Streets, in 1849. Krug steadily expanded and industrialized his brewing operations and hired Joseph Schlitz, newly arrived from Mainz, Germany, as his bookkeeper in 1850. Schlitz bought the brewery after Krug died unexpectedly in 1856, and married his widow in 1858.[1]

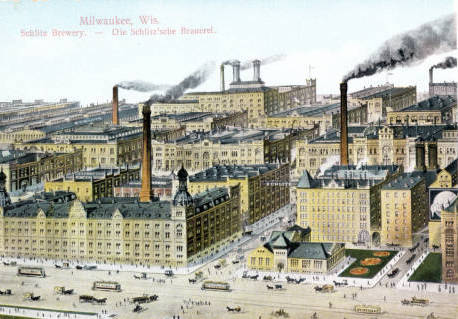

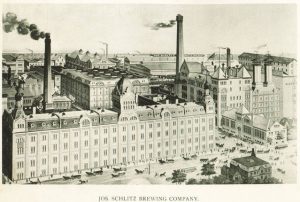

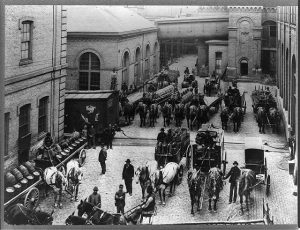

Under Schlitz’s leadership, the company built a new, larger brewery on Third and Walnut Streets in 1870.[2] The new site allowed for greater immediate production capacity and expanded into a sprawling, multi-block complex by the 1890s.[3]

Like other major Milwaukee brewers, Schlitz benefited immensely from the nearby Chicago market, opening an agency there in 1868.[4] The Great Chicago Fire of 1871 temporarily destroyed the local brewing industry, and Schlitz more than doubled sales over the next year.[5]

Schlitz incorporated in 1873, and the Uihlein family (of the Krug line) took over control of the company after Schlitz’s death in a shipwreck in 1875. Retaining the Schlitz name, the Uihleins stayed in control of the company until Robert Uihlein, Jr. died in 1976, three generations later.[6]

Schlitz employed a wide array of scientific, technological, and marketing innovations to standardize their product and compete for leadership of the national market. In 1883 William J. Uihlein brought the first pure culture yeast strain to the United States from Copenhagen, which allowed Schlitz to produce a higher quality beer more consistently.[7] Schlitz helped establish the Union Refrigerator Transit Company in the 1890s, with Joseph Uihlein, Sr. as president, to develop and operate a more cost-effective refrigerated freight line for the brewery.[8] Schlitz was the first to introduce the brown bottle to industrial brewing in 1911, which protected the beer from the harmful effects of light during shipping.[9] Between the late 1870s and early 1900s, Schlitz invested heavily in building and maintaining “tied house” saloons in Milwaukee and beyond, and also established other significant Milwaukee leisure spots, like the Schlitz Park beer garden (1879) on Eighth Street near Walnut; the Schlitz Hotel (1890); the Schlitz Palm Garden (1895); and the Uihlein (later Alhambra) Theater (1896) downtown.[10] Schlitz first introduced its belted globe logo in 1892 and its memorable slogan, “The beer that made Milwaukee famous,” in 1894.[11] In 1898, Schlitz sent highly publicized gifts of beer to Admiral George Dewey’s men after their victory in Manila during the Spanish-American War and to Theodore Roosevelt’s hunting party in Africa.[12] These moves paid off as Schlitz passed Pabst as the largest brewer in United States by 1902.[13]

Schlitz restructured their operations to survive Prohibition, producing malt syrup, bakery products, and sodas, among other items, including a short-lived “Eline” chocolate and candy division on N. Port Washington Road in present day Glendale.[14]

Schlitz returned to its position as a national brewing leader after the repeal of Prohibition in 1933, becoming the largest American brewery again by 1947, and remained in either first or second place until the mid-1970s.[15] The company continued to expand through the 1950s and 1960s.[16] By the late 1960s, Schlitz had added plants in Brooklyn, Kansas City (Missouri), Tampa, San Francisco, Van Nuys (California), and Longview (Texas), as well as affiliates in San Juan (Puerto Rico), and Seville, Barcelona, and Madrid (Spain).[17] Schlitz developed innovative television marketing campaigns in the 1960s with the slogans, “Real gusto in a great light beer,” and “When you’re out of Schlitz, you’re out of beer.”[18] The company continued to make civic contributions to Milwaukee in the 1960s and 1970s, including the downtown Performing Arts Center (with the main Uihlein Hall), the Schlitz Audubon Nature Center, the Great Circus Parade, and the Streets of Old Milwaukee exhibit at the Milwaukee Public Museum.[19]

Despite its success, the company stumbled in the late 1960s. In 1967, Schlitz introduced a more efficient brewing process called “accelerated batch fermentation.” While allowing for a lighter beer to be produced at lower costs, consumers believed the change was made at the expense of the beer’s quality.[20] Schlitz also experienced a major problem with “flaky” or “hazy” beer due to a production problem in 1976. Although it was “perfectly safe” to drink, the beer looked tainted. Schlitz officials did not act on the problem until sales had already begun plummeting, unsuccessfully attempting to recall and discard the bad batches secretly.[21] Leadership was transferred out of the Uihlein family for the first time after the death of Robert Uihlein, Jr. in 1976.[22] In 1981, Schlitz attempted to reduce production costs by forcing concessions on its workers, who went on strike. Contract negotiations broke down. The Schlitz board closed the Milwaukee plant, and sold out to the Stroh Brewing Company in 1982.[23]

The Schlitz brand lives on in the portfolio of the Pabst Brewing Company. The brewery complex was redeveloped into the Schlitz Park Office Center in the mid-1980s.[24]

Footnotes [+]

- ^ Jerry Apps, Breweries of Wisconsin (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1992), 102; Susan K. Appel, “Building Milwaukee’s Breweries: Pre-Prohibition Brewery Architecture in the Cream City,” Wisconsin Magazine of History 78, no. 3 (Spring 1995): 168-169; Wilhelm Otto Keller, “From Miltenberg to Milwaukee: Beer Magnates from the Lower Main Area in the United States in the Nineteenth Century,” trans. Michael R. Reilly, March 28, 2013, last accessed October 4, 2016.

- ^ Apps, Breweries of Wisconsin, 102; Thomas C. Cochran, The Pabst Brewing Company: The History of an American Business (New York: New York University Press, 1948), 54-57.

- ^ Appel, “Building Milwaukee’s Breweries,” 175-182.

- ^ Perry R. Duis, The Saloon: Public Drinking in Chicago and Boston, 1880-1920 (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1983), 18-19.

- ^ Cochran, Pabst, 55-56; Apps, Breweries of Wisconsin, 102.

- ^ Apps, Breweries of Wisconsin, 102-103; Stanley Baron, Brewed in America: A History of Beer and Ale in the United States (Boston: Little, Brown, 1962), 288; Uwe Spiekermann, “Marketing Milwaukee: Schlitz and the Making of a National Beer Brand, 1880-1940,” Bulletin of the German Historical Institute, no. 53 (Fall 2013): 56; Michael R. Reilly, “Uihlein Family History / Genealogy 1,” Sussex-Lisbon Area Historical Society, Inc., January 17, 2000, last accessed October 4, 2016.

- ^ Baron, Brewed in America, 240; Bayrd Still, Milwaukee: The History of a City (Madison: State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1948), 330.

- ^ Baron, Brewed in America, 259-260; Michael R. Reilly, “Schlitz Refrigerated Box Cars or Reefers Plus History Behind,” Sussex-Lisbon Area Historical Society, Inc., January 15, 2000, last accessed October 4, 2016.

- ^ Spiekermann, “Marketing Milwaukee,” 60.

- ^ Authorities differ on some of these dates. We have chosen to rely on the Milwaukee Public Library and Milwaukee Journal’s claim that the Schlitz Hotel and Palm Garden were established in 1890 and 1895 respectively, rather than other sources that cite 1886, 1889, or 1896 as possible years for their establishment. Cochran, Pabst, 145; Spiekermann, “Marketing Milwaukee,” 57; Still, Milwaukee, 403-404; Baron, Brewed in America, 272; “Milwaukee Historic Photos: Schlitz Hotel,” Milwaukee Public Library, accessed January 6, 2016; Walter Monfried, “Milwaukee’s Most Elegant Saloon,” Milwaukee Journal, October 12, 1964, sec. 1, p. 16; “Sentinel Files,” Milwaukee Sentinel, December 20, 1971, sec. 1, p. 24.

- ^ While Spiekermann claims that the belted globe logo and “The Beer that Made Milwaukee Famous” slogan were introduced in 1892 and 1894 respectively, the company website claims that they were introduced as early as 1886 and 1893. We have chosen to rely on Spiekermann’s scholarship here. Spiekermann, “Marketing Milwaukee,” 58; “History,” Schlitz Brewing Company, accessed January 6, 2016.

- ^ Still, Milwaukee, 332-333.

- ^ John D. Buenker, The History of Wisconsin, vol. 4, The Progressive Era, 1893-1914 (Madison: State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1998), 112; Spiekermann, “Marketing Milwaukee,” 56.

- ^ Baron, Brewed in America, 314; Spiekermann, “Marketing Milwaukee,” 64; Michael R. Reilly, “Joseph Schlitz Brewing Co.: A Chronological History, 1907-1933,” last revised August 16, 2015, last accessed October 4, 2016.

- ^ Apps, Breweries of Wisconsin, 103-109.

- ^ Ibid., 104.

- ^ Jos. Schlitz Brewing Company, 1966 Annual Report (Milwaukee: Jos. Schlitz Brewing Company, 1966), 10; Michael R. Reilly, “Joseph Schlitz Brewing Company: A Chronological History, 1933-1969,” last revised August 16, 2015, last accessed October 4, 2016.

- ^ Apps, Breweries of Wisconsin, 105.

- ^ Ibid., 105-106; Dorothy Kincaid, “Have You Heard?,” Milwaukee Sentinel, January 8, 1965, sec. 1, 4; “New Museum Wing Revives Memories,” Milwaukee Journal, January 16, 1965, sec. 1, 7.

- ^ Ibid., 108-109.

- ^ Jacques Neher, “What Went Wrong, Part II,” Milwaukee Journal, June 9, 1981, sec. 2, 9; Apps, Breweries of Wisconsin, 109.

- ^ Apps, Breweries of Wisconsin, 109; Jos. Schlitz Brewing Company, 1976 Annual Report (Milwaukee: Jos. Schlitz Brewing Company, 1976), 2-3.

- ^ Lawrence C. Lohmann, “Schlitz Strike Raises Fears about Future Here,” Milwaukee Journal, June 1, 1981, sec. 1, 1, 12; Apps, Breweries of Wisconsin, 109-111.

- ^ “Pabst Brewing Company Beers,” accessed May 31, 2014; Thomas Collins, “$15 Million Plan Set for Schlitz Site,” Milwaukee Sentinel, May 7, 1985, sec. 1, 1, 6.

For Further Reading

Apps, Jerry. Breweries of Wisconsin. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1992.

Spiekermann, Uwe. “Marketing Milwaukee: Schlitz and the Making of a National Beer Brand, 1880-1940.” Bulletin of the German Historical Institute 53 (Fall 2013): 55-67.

0 Comments

Please keep your community civil. All comments must follow the Encyclopedia of Milwaukee Community rules and terms of use, and will be moderated prior to posting. Encyclopedia of Milwaukee reserves the right to use the comments we receive, in whole or in part, and to use the commenter's name and location, in any medium. See also the Copyright, Privacy, and Terms & Conditions.

Have a suggestion for a new topic? Please use the Site Contact Form.