The most remarkable reminder of the presence of veterans in Milwaukee is the Milwaukee County War Memorial Center (WMC), which was built on the downtown lakefront as a “living memorial” to veterans. Finished in 1957, the War Memorial building is the home of the Milwaukee Art Museum, while the non-profit organization that administers the WMC provides office space for a number of veterans’ organizations, sponsors the annual Memorial Day parade, and hosts lectures, exhibitions, and events related to veterans and community issues.[1] Another veterans-related landmark is the gothic-looking building on the bluff looming over Miller Park’s right-field fence; it is the main building of the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers, built in the 1860s to care for disabled Civil War soldiers. A cluster of perhaps twenty other buildings from the 1870s and 1880s surround it, while the Clement J. Zablocki VA Medical Center is located just south and down the hill from the historic buildings.

However, Milwaukee-area veterans pre-date the War Memorial by more than a century and the National Home by nearly three decades. At least two Revolutionary War veterans who came to the Wisconsin the late 1830s or early 1840s are buried in the Milwaukee area, one in Wauwatosa and the other in Brookfield.[2] A scattering of veterans of the War of 1812 also ended up in Wisconsin, including one who died and was buried in Wauwatosa.[3] And a few Wisconsinites served in the Mexican-American War. In 1877 the National Association of Veterans of the Mexican War reported 117 Mexican War veterans living in Wisconsin, out of a national total of 6,250.[4]

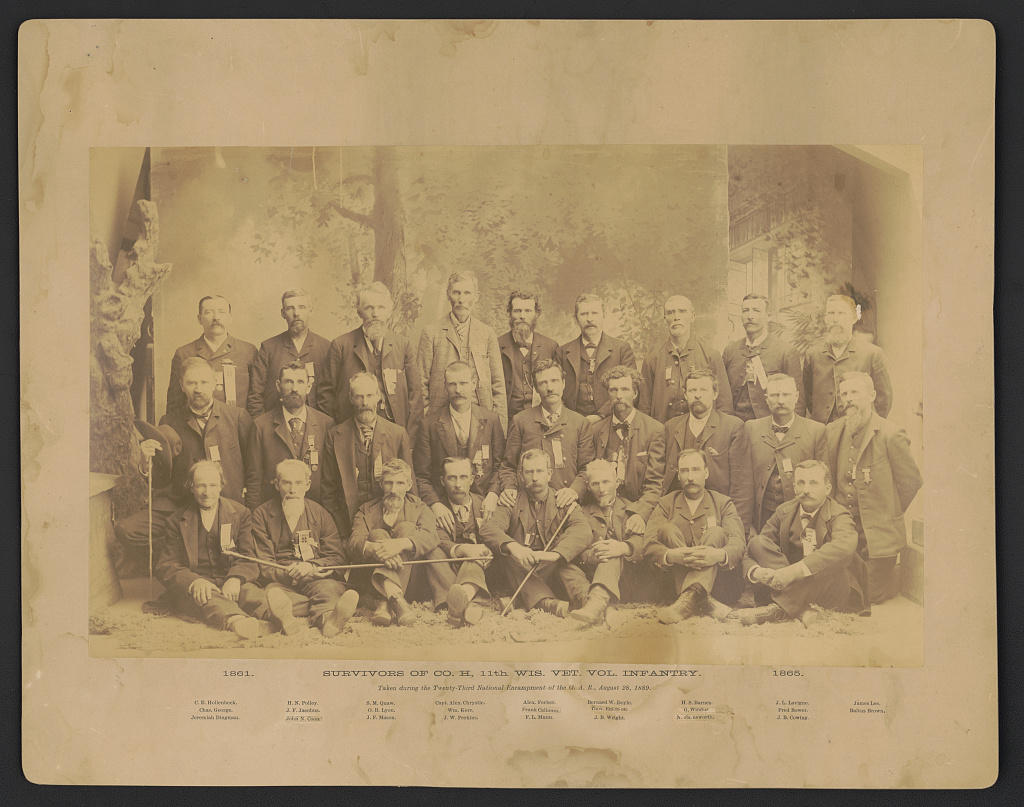

The first group of veterans to have a visible presence in Milwaukee were survivors of the Civil War. Although Civil War veterans founded a number of organizations, the largest and most influential was the Grand Army of the Republic (GAR), which was formed soon after the war. The first GAR group in Milwaukee, Phil Sheridan Post, No. 3, was chartered July 31, 1866. Other notable posts from this early period were Robert Chivas Post, No. 2, and Veteran Post, No. 8, organized at the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers. As it did nationally, the GAR movement nearly died out in Wisconsin in the 1870s. That changed in 1879, when a group of ex-soldiers began planning a reunion for Wisconsin soldiers for the next year. The invitation was extended to veterans from all over the north, and thousands responded to pleas like the one that appeared in a circular promoting the event. It commanded “Comrades” to come to Milwaukee, “or we shall not know whether you are dead, proud or gone to Texas.” An estimated 100,000 veterans—including Generals U. S. Grant and Phil Sheridan—along with even more friends and family members swarmed to Milwaukee, which had put up $40,000 to support the reunion. Within a few years, membership had soared to over 400,000.[5]

Nationally, the GAR successfully promoted the expansion of the Civil War pension system, which by the 1890s was paying out nearly $147,000,000 a year (43 percent of the federal budget) to perhaps half a million union veterans.[6]

Between 1880 and 1889, when the GAR once again held its national encampment in Milwaukee, scores of posts had been formed in Wisconsin. Eventually more than 400 would be chartered. Milwaukee’s E. B. Wolcott Post, No. 1, which met for many years in the Academy of Music, became the largest post in the state, eventually admitting over 700 veterans who had served in virtually all of Wisconsin’s regiments and in units from twenty other states. At least eight other posts were established in Milwaukee, and posts were also chartered in Waukesha, Oconomowoc, Hartford, West Bend, and Cedarburg. In 1915, the public library’s Memorial Hall—now called Centennial Hall—became a museum of sorts to display GAR memorabilia, flags, and portraits. Together with their comrades throughout the state, Milwaukee area GAR men helped establish the Wisconsin Veterans Home in King, promoted the flying of American flags over public schools, organized Memorial Day commemorations, delivered patriotic lectures to schoolchildren, and maintained charitable initiatives for fellow veterans. Allied with the GAR was the Milwaukee Sunday Telegraph, which in the 1880s promoted Civil War veterans by publishing hundreds of war stories written by old soldiers, announcing local, state, and national GAR events, and printing brief news pieces on individual veterans. By 1920 only Wolcott Post was still active; most Civil War veterans had died, of course, by the time of the Second World War. The annual encampment of the state GAR was held in Milwaukee or at the National Home a dozen times between 1867 and 1900, while Milwaukee hosted two additional national encampments, in 1923 and 1943, when the national GAR had less than 400 members and only a handful of old soldiers showed up.[7]

Although the GAR passed its legacy on to the still-active Sons of Union Veterans (local posts commemorate their ancestors with Memorial Day events and historical lectures), GAR posts began to die off during first decades of the twentieth century, just as a new group formed that would eventually become the most important veterans organization of the twentieth century: the American Legion.[8] Formed by American soldiers stationed in Europe just after the First World War, the American Legion became the largest veterans’ organization of the twentieth century. Unlike the GAR, the Legion eventually opened its membership to all who had served honorably in the armed services during times of war, including undeclared conflicts in Korea, Vietnam, Iraq, and Afghanistan, and the war on terror.[9] Once the veterans of the Second World War began joining, membership rose to over three million in 1946; it remained at just under through the end of the twentieth century.[10]

The American Legion naturally focused on issues related to the physical and economic welfare of veterans. It led the movement to create the US Veterans Bureau (the predecessor of the Veterans Administration) in 1921, lobbied for the educational benefits provided by the 1944 GI Bill, contributed to the Vietnam War Memorial, funded research into the effects of Agent Orange on veterans, and promoted other programs designed to aid the families of veterans, to investigate health issues related to veterans, and to promote patriotism in the schools.[11]

Milwaukee veterans were part of the Legion from the beginning. The American War Veterans of Wisconsin held a convention in Milwaukee in January 1919 that led to an affiliation with the national organization. The first post in Wisconsin, Arthur Kroepfel Post #1, was chartered in Milwaukee on June 11, 1919; two weeks later Milwaukee’s George Washington Post #2 was chartered. The city saw a number of “firsts” in Wisconsin Legion history. In 1937 Jane Delano Post #408 became one of the first posts for female veterans in the nation, while in 1964 the region’s first Hispanic branch, David Valdes Post #529, was formed.[12]

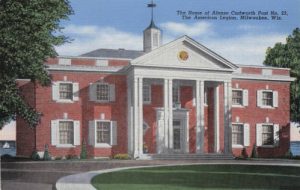

Alonzo Cudworth Post #23 was the state’s largest post and included as members such luminaries as Generals Douglas MacArthur and Billy Mitchell. At its height in the 1980s it had 5,000 members and met in a mansion on Prospect Avenue; by 2014, the four hundred or so members met in rooms above a restaurant in Glendale. Its legacies include helping to start Badger Boys State, which has been held each summer since 1939—aside from a recess during the Second World War—with the mission to educate boys about democratic and political processes.[13] In the 1950s they also sponsored American Legion baseball teams, which in Wisconsin and elsewhere became a training ground for many major baseball players; in 2015 there were still over 200 teams in the state.[14] And its men’s chorus won the national American Legion competition several times in the 1950s.[15] Cudworth Post continues to provide honor guards for veterans’ funerals and to conduct educational programs.[16]

The Veterans of Foreign Wars, formed in the early twentieth century by veterans of the Spanish American War and the so-called Philippine Insurrection, limits eligibility to veterans who have served abroad. According to its website, members must have “received a campaign medal for overseas service…or received hostile fire or imminent danger pay.” Korean War-era veterans need to have served for a certain number of days in Korea. Other than its narrower membership base, the VFW shares many of the same interests as the American Legion, particularly veterans’ health, the commemoration of notable military milestones, and patriotic education. In addition, like American Legion posts, VFW posts offer opportunities for socializing for veterans and their families. Several Milwaukee-area VFW posts feature club rooms, complete with full-service bars and Friday night fish fries.[17] In 2016 there were just under fifty Veterans of Foreign Wars posts in Milwaukee, Washington, Ozaukee, and Waukesha Counties.[18]

Much smaller than either the Legion or VFW is AMVETS, originally limited to veterans of the Second World War, but since the 1980s open to all veterans. Only a few posts still exist in the Milwaukee area; AMVETS is one of the organizations headquartered at the Milwaukee County War Memorial Center.[19]

Other veterans’ organizations in the Milwaukee area have tended to focus on specific health concerns or political interests. In the 1980s, the Disabled American Veterans organized groups in Milwaukee, West Allis, Waukesha, New Berlin, and Hartford; the Wisconsin Paralyzed Veterans of America opened a Milwaukee chapter around the same time.[20] A very different organization appeared in 1967, when Vietnam Veterans Against the War emerged nationwide and in Milwaukee. Even with the end of its namesake war, the VVAW continued to oppose American military interventions, to provide support networks for veterans who are homeless or suffering from PTSD, and to publish The Veteran, a semi-annual newsletter.[21] A more recent organization, Veterans for Peace—Milwaukee’s chapter is VFP 102—declares on its website that it has been “Exposing the True Costs of War and Militarism Since 1985.”[22] Other organizations dedicated to helping veterans include the Milwaukee Homeless Veterans Initiative, which provides food and housing for homeless veterans and their families. Dryhootch offers a drug-free social and support network for returning combat veterans from a Brady Street coffee shop and several other locations.[23]

Although the American Legion and other modern organizations have admitted female members for many years, most of the major veterans’ organizations also established auxiliaries for women who supported the mission of the larger organization. The Women’s Relief Corps supported the Grand Army of the Republic by promoting Memorial Day commemorations and doing volunteer work at state and federal soldiers homes. In Milwaukee, they were particularly active at the Northwestern Branch of the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers.[24] The American Legion Auxiliary, founded the same year as the Legion itself, has raised money for health and social programs, many, but not all, related to veterans issues. In Wisconsin, they also sponsor Badger Girls State, manage poppy sales in the days leading up to Memorial Day, and distribute scholarships. Virtually every post has an auxiliary; nation-wide there are nearly a million members in over 10,000 posts.[25] As of 2016, nearly 1,200 women belonged to the Auxiliary posts in the Milwaukee area.[26]

Footnotes [+]

- ^ “History,” Milwaukee County War Memorial Center Website, last accessed May 15, 2017.

- ^ Milwaukee Journal, May 30, 1959. Lisa Sink, “Descendants, City Honor Revolutionary War Veteran Buried in Brookfield,” Brookfield Patch, May 29, 2012, last accessed May 15, 2017.

- ^ Milwaukee Sentinel, September 17, 1934, last accessed May 15, 2017.

- ^ “Fourth Annual Reunion” of National Association of Veterans of the Mexican War (Washington: Thomas J. Brashears, 1877), 10.

- ^ Larry Logue, To Appomattox and Beyond: The Civil War Soldier in War and Peace (Chicago, IL: Ivan R. Dee, 1995), 94-95.

- ^ James Marten, Sing Not War: The Lives of Union & Confederate Veterans in Gilded Age America (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2011), 17.

- ^ Thomas J. McCrory, Grand Army of the Republic: Department of Wisconsin (Madison, WI: Wisconsin Veterans Museum Foundation, 2005), 91; Stephen A. Michaels, “The Grand Army of the Republic in Milwaukee,” last accessed May 15, 2017; “Wisconsin Grand Army of the Republic Posts,” Wisconsin Veterans Museum; Marten, Sing Not War, 147-148; “Wisconsin Grand Army Encampments,” Wisconsin Veterans Museum, last accessed May 15, 2017; McCrory, Grand Army of the Republic, 322-323.

- ^ “Homepage,” Sons of Union Veterans, last accessed May 15, 2017.

- ^ “History: The American Legion,” last accessed May 15, 2017

- ^ “American Legion,” Encyclopedia.com, last accessed May 15, 2017.

- ^ “History,” American Legion, last accessed May 15, 2017.

- ^ George E. Sweet, The Wisconsin American Legion: A History, 1919-1992 (Milwaukee: Wisconsin American Legion Press, 1992), 4, 6, 32, 131.

- ^ “Homepage,” Badger Boys State, last accessed May 15, 2017.

- ^ “American Legion Baseball,” The American Legion Department of Wisconsin, last accessed May 15, 2017.

- ^ Loren Osman, “Cudworth Post Sings Its 10th Anniversary Song,” Milwaukee Journal, October 30, 1957.

- ^ Meg Jones, “Memories Fade, but 2 Legion Posts Try to Retain World War I Legacies,” Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, July 26, 2014.

- ^ “Eligibility,” Veterans of Foreign Wars, last accessed May 15, 2017.

- ^ “Homepage,” Veterans of Foreign Wars, http://vfwofwi.com/. Information now available at http://vfwwi.org/, last accessed May 15, 2017

- ^ “History,” AMVETS Department of Wisconsin, last accessed May 15, 2017.

- ^ Encyclopedia of Associations: Regional, State, and Local Organizations. Vol., Great Lakes States (Detroit, MI: Gale Research Co., 1988/89), 1135, 1206, 1125, 1154, 1074.

- ^ Newsletter, The Veteran, last accessed May 15, 2017.

- ^ Homepage, Veterans for Peace, https://www.veteransforpeace.org/vfp-chapters/find-a-chapter/vfp-102-milwaukee/. This information is now available at https://www.veteransforpeace.org/, last accessed May 15, 2017.

- ^ “Our Story,” http://www.mkehomelessvets.org/index.html, now available at http://www.mkehomelessvets.org/history.htm, last accessed May 15, 2017; “About,” Dryhootch, last accessed May 15, 2017.

- ^ “Grand Army of the Republic, Woman’s Relief Corps and Sons of Veterans, U.S.A., General Orders, 1888-1912,” Chronicling Illinois, Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library & Museum, last accessed May 15, 2017.

- ^ “American Legion Auxiliary,” American Legion Auxiliary, last accessed May 15, 2017; “American Legion Auxiliary, Department of Wisconsin,” last accessed May 15, 2017.

- ^ “2016 Membership Totals Processed as of June 28, 2016,” last accessed May 15, 2017.

For Further Reading

Kinder, John M. Paying with Their Bodies: American War and the Problem of the Disabled Veteran. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2015.

Larsen, Sarah A., and Jennifer M. Miller. Wisconsin Korean War Stories: Veterans Tell Their Stories from the Forgotten War. Madison: Wisconsin Historical Society Press, 2008.

Larsen, Sarah A., and Jennifer M. Miller. Wisconsin Vietnam War Stories: Our Veterans Remember. Madison: Wisconsin Historical Society Press, 2010.

McCrory, Thomas J. Grand Army of the Republic: Department of Wisconsin. Madison: Wisconsin Veterans Museum Foundation, 2005.

Pencak, William. For God and Country: The American Legion, 1919-1941. Boston: Northeastern University Press, 1989.

0 Comments

Please keep your community civil. All comments must follow the Encyclopedia of Milwaukee Community rules and terms of use, and will be moderated prior to posting. Encyclopedia of Milwaukee reserves the right to use the comments we receive, in whole or in part, and to use the commenter's name and location, in any medium. See also the Copyright, Privacy, and Terms & Conditions.

Have a suggestion for a new topic? Please use the Site Contact Form.