“Milwaukee is a workingman’s city,” wrote Frank Flower in his massive 1881 History of Milwaukee. Flower described a community of tradesmen, machinists, and laborers where a typical worker could enjoy, even on wages of a dollar or two a day, “good air, good water, cheap living, and a chance to found a home of his own.”[1]

The Victorian historian’s portrait of Milwaukee as a blue-collar industrial capital, a stereotype that has endured for generations, is accurate to an extent, but it reflects only one understanding of work in a single historical period. The concept of work is both more dynamic and considerably broader than Flower suggested. Reduced to its essentials, work may be defined as any form of life-supporting activity, or, less succinctly, as the diverse means by which individuals achieve and maintain a standard of living and thereby participate in the economy of the society around them. Stated even less formally, work is what grown-ups do all day if they are not independently wealthy.

For Milwaukee’s first residents, work was necessarily oriented to the resources at hand. The land itself provided Native Americans with all the materials they needed to make a living, and work, for them, involved converting those materials to food, shelter, clothing, and other necessities. Saplings, bark, roots, sap, and flowering wild plants from the area’s abundant woodlands were turned into wigwams, canoes, cradleboards, maple sugar, dyes, berries, medicine, and a host of other useful items. Local wetlands supplied the native tribes with reeds and rushes for mats and baskets, fish and waterfowl for protein, and wild rice for nutrition through the long northern winters. Fur-bearing animals were hunted not only for their meat but also for skins that became clothing and for claws, teeth, and quills that became adornments. The earth itself yielded clay for pottery, powdered soil for pigments, and siliceous stones for fire-starters and projectile points.[2]

There was one area of activity in which Milwaukee’s first peoples worked beyond the resources at hand: agriculture. Food plants developed in Mesoamerica made their way north over the centuries, and every local village had its adjacent garden plots. Antoine le Clair, a fur trader interviewed in 1868, described the native landscape of pre-urban Milwaukee:

The Indians at Milwaukee would cultivate not to exceed five or six acres to a family—mostly sweet corn, pumpkins, beans, melons and a few potatoes. They would have to fence in their fields against their horses….They would fence rudely, with bushes, poles and brush—sometimes poles fastened to bushes. They used no plows; they would only hoe the ground.[3]

Worked intensively over many generations, native garden plots became conspicuous landscape features. Milwaukee’s largest agricultural site sprawled across the present intersection of Lincoln Avenue and S. Layton Boulevard (Twenty-seventh Street) on the city’s South Side. Called Indian Fields by early white settlers, it covered well over 100 acres—a significant holding even by modern standards. Corn was the dominant crop at Indian Fields, and the chief of the adjoining village was named Oseebwaisum, or Cornstalk.[4]

Like the Native Americans they displaced, the first white settlers worked the land, but they also worked against it. Without the technologies to remake the landscape they inhabited, local tribes had preserved it in a state of nature, but the aspiring Yankee farmers of the 1830s worked hard to denature it. Their first task was to clear the land of its abundant forest cover, and many a pioneer developed a lasting antipathy to trees. Wisconsin historian Joseph Schafer described them as “oppressively plentiful.”[5] Christian Wahl, an early leader of Milwaukee’s park movement, explained why there was practically no public green space when he arrived in 1847: “As people then thought, we had parks with a vengeance, for to a man who has to raise corn and pork to feed his family a tree is looked upon as a mortal enemy, whom to subdue means the hardest kind of labor.”[6]

Although clearing continued into the late 1800s, Milwaukee County, including most of today’s city, was a checkerboard of 1,184 farms by 1849, one year after Wisconsin attained statehood.[7] Where trees had stood, a monoculture of wheat took root. The county’s farmers harvested 61,000 bushels of the grain in 1849, and their work resolved to the yearly round of tilling, planting, cultivating, reaping, and then resting for the next turn of the cycle. It was a cycle, wrote Joseph Schafer, of unremitting labor:

We speak of the day when practically all farm work was hand work, when cultivating was with the hoe, mowing with the scythe, reaping with the sickle or the cradle, binding and husking with the fingers, pitching with the two-tined fork. No relief could the harassed farmer find from the compulsory program of toiling “the livelong day” in order to eke out a livelihood for the family.[8]

Farm products not consumed locally were shipped through the port of Milwaukee to waiting markets in the East and Europe, the same markets that sold finished goods to the nascent frontier settlement. As Milwaukee developed in tandem with its agricultural hinterland, one feeding the other, the classic urban division of labor emerged. Family farms dominated the rural areas, while work in the city became both more diverse and more specialized. The very act of converting native woodlands and wetlands to a city required prodigious effort. Nelson Olin, a carpenter with roots in New York State, spent the entire summer of 1836 building E. Wisconsin Avenue from the river to the lake bluff, a distance of seven blocks. The project involved traveling to New York for carts, scrapers, shovels, pickaxes, and horses; assembling a crew of local laborers; filling a forty-foot ravine at Broadway; and clearing a dense woods on the lake bluff that ended up as fill. Olin was paid $3,000 for his labors, and, he said, “A harder job never was done in Milwaukee for the same money.”[9]

There was no shortage of other outlets for manual labor. Legions of workers were needed to fill in swamps, build plank roads, lay railroad tracks, grade streets, load and unload ships, and install water pipes and sewer lines. Such entry-level jobs were typically filled by European immigrants, who constituted a majority of Milwaukee’s population before 1850. Manual labor provided a foothold for newcomers from Ireland, the United Kingdom, Bohemia, and Scandinavia, but Germans, as the city’s largest ethnic group, were most numerous among the laboring classes. “The average Milwaukee ditchdigger,” wrote Kathleen Neils Conzen, “was ‘Dutchman’ and not ‘Paddy.’”[10]

Working with their backs and hands, Milwaukee’s immigrant laborers created an urban infrastructure that supported a comprehensive range of other occupations. Merchants sold groceries, dry goods, and hardware. Craftsmen made shoes, barrels, and harnesses. Professionals treated fevers and filed lawsuits. Tanners, millers, butchers, and brewers plied their various trades. Whether they spent their workdays tending stores, hammering nails, figuring sums, cutting leather, or writing sermons, Milwaukee’s workers existed in a fluid symbiosis, each in some way making it possible for the others to earn a livelihood.

At the center of this interdependent web were the capitalists who added economic mass to the city and fueled its expansion. No one played a larger role in that sphere than Alexander Mitchell, a Scottish immigrant who arrived in 1839 and became a regional power in banking, railroads, insurance, and the grain trade. One of his contemporaries described Mitchell’s daily round in the 1880s:

During the last ten or twelve years of his life the casual observer might readily have set him down as a gentleman of leisure. At a reasonably early hour in the morning he would put in an appearance at the bank, examine his mail, and give brief attention to any matter that required it. In a little while he would take a stroll through the railroad offices, and then perhaps step in to have a little chat with the officers of the Insurance Company, all in a leisurely, unconcerned sort of a way, as if he had no business in particular to look after and was making a friendly call. Yet you may be sure he had a perfect understanding of what was going on in all those institutions, and was fully competent to advise or direct when occasion arose.[11]

The rise of a capitalist elite was accompanied by a shift in the popular understanding of what constituted work. Alexander Mitchell and his fellow business titans came to associate it with manual labor, a field of activity worlds removed from their deal-making and financiering. Eber Brock Ward, a Detroit entrepreneur who (with Mitchell’s help) established an iron mill on Milwaukee’s south lakefront in 1868, made the point clearly in a letter read to his assembled employees at an 1872 banquet: “I have never lost my interest in the welfare of the hard workers of the country, since I once earned my own living, fishing and rowing.”[12] Ward’s suggestion that he had ceased to be a worker when money became his primary tool revealed a growing separation between capital and labor.

It was not only the understanding of work that changed but the nature of work itself. As Milwaukee’s first heavy industry, Eber Ward’s own enterprise marked a sea change in the local economy. His Milwaukee Iron Company covered more than eighty acres at what is now the south end of the Daniel Hoan Bridge. In its shadow developed a company town called Bay View, which had a brief career as an independent suburb before joining the City of Milwaukee in 1887. The rolling mill became the second-largest producer of railroad rails in America, employing up to 1,500 men during periods of peak production. Those workers had specific tasks—puddler, heater, pickler, annealer, and many others, including laborer—but none filled more than a small niche in a plant whose furnaces, rolling stands, and pouring equipment were built on the massive scale. Gone were the cottage industries and home crafts of the pioneer period. Dwarfed by their surroundings, mill hands took a giant step away from hand work to a new order based on machine work.[13]

Conditions in this first stage of industrialization were particularly harsh. Workers at the Bay View mill routinely put in ten to twelve hours a day, six days a week, in a complex that was literally hell on earth. The Milwaukee Sentinel sent a reporter to the plant during an 1881 hot spell. He found workers toiling bare-chested in temperatures of 160 degrees, with grimy Turkish towels wrapped around their necks to soak up sweat and leather straps fastened to their boots to prevent burns from spilled iron. The reporter seemed incredulous:

None but the men who have worked in these great hives of human industry, among immense furnaces and molten and seething metal, have any conception of the heat which a mill-hand has to endure while at his hard and tedious labor.

The Sentinel scribe doffed his hat to Bay View’s men of iron who, he concluded, “become red hot and yet do not melt.”[14]

Built for high-volume production, the Bay View iron mill was a mechanical marvel from the day it opened. As industrialization proceeded, machines took over other jobs that had long depended on hard-won hand skills. Shop by shop, trade by trade, a new system took hold that redefined work for the broad spectrum of Milwaukeeans. Emil Seidel, who became the city’s first Socialist mayor in 1910, was a woodcarver by trade. During his days in a North Side furniture factory, Seidel witnessed the poignant passing of an age:

Every time a machine was installed to do what machines had never done before, the cabinet makers and carvers came, singly or in twos, to see the work it did, untiringly, as fast as the hand fed it—“oh, so much faster than at the bench.” They took a piece to see better and feel of it—“how smooth, through knots and everything.” The machine-hand grinned, proud of his work, with eyes sparkling. With the victory of the machine he was coming up. Quietly, the others slunk back to their benches. They were licked.[15]

By the late 1800s, labor had increasingly become a commodity, one more input in a long list that included raw materials, fuel, and office supplies. Newcomers straight off the boat could be trained in a matter of days to perform tasks that had once required years of patient application. As a direct result, occupational hierarchies collapsed and the contract theory of labor reigned supreme. Jeremiah Rusk, Wisconsin’s governor from 1882 to 1889, spoke plainly of the owner’s right to run his factories and the workers’ right to sell him their time and labor. “Where one person engages to work for another,” Rusk declared in 1887, “on another’s premises and material, and with another’s tools or machinery…the product belongs to the employer; the workman’s claim ends with the receipt of his stipulated wages.”[16]

In growing numbers, Milwaukee’s workmen begged to differ. Fed up with what they perceived as inadequate wages and hazardous working conditions, a majority of Milwaukee’s industrial workers went on strike during the first week of May 1886. Marching behind the banner of the Knights of Labor, a national union with a formidable local presence, they campaigned for an eight-hour day without a cut in pay. Striking workers virtually shut down the city, prompting Gov. Jeremiah Rusk to call out the militia. By the morning of May 5, only one major employer remained open: the Bay View iron mill. When a crowd of 1,500 strikers, most of them Polish immigrants, marched on the mill that morning, they found the militia waiting for them. At a distance of roughly 200 yards, the troops opened fire, killing an estimated seven marchers. It was the bloodiest labor disturbance in Wisconsin’s history.[17]

The 1886 shootings quelled the immediate uprising, but they had the unintended effect of galvanizing industrial workers to organize politically. A People’s Party rose from the ashes of the eight-hour movement and virtually swept the fall elections of 1886; a millwright named Henry Smith went to Washington as the people’s representative in Congress. Although a fusion ticket of Republicans and Democrats retired the populists in the next cycle, a giant had been awakened. The events of 1886 proved to be a watershed in the city’s history, paving the way for the Socialist sweep of 1910 and fueling a continued campaign for workers’ rights.[18]

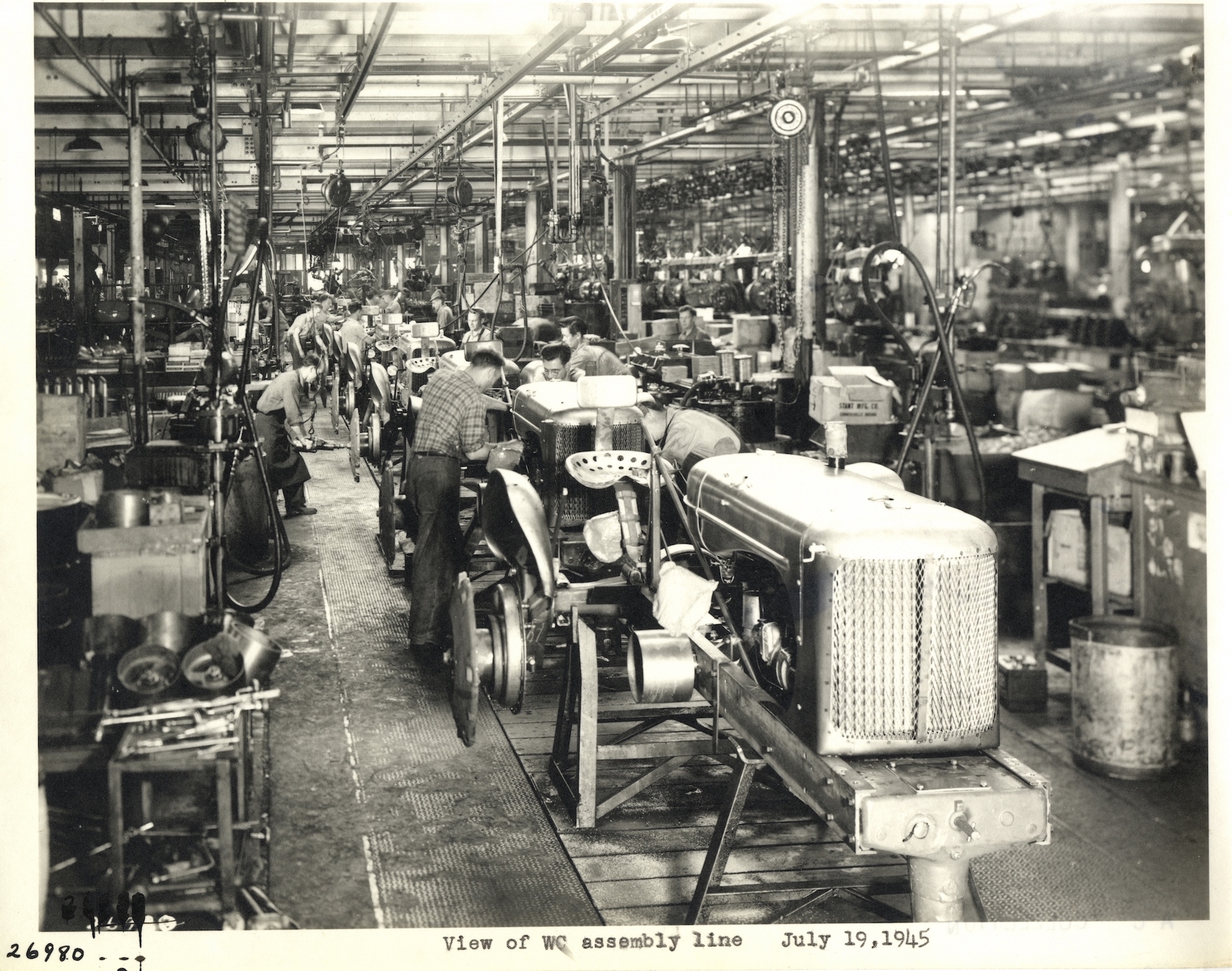

The growth of Socialism and the rise of the labor movement are separate sagas, but both rose from roots in the workplace. Milwaukeeans remained at their jobs all the while, in every occupational category. The city remained the state’s commercial capital, with a vigorous retail trade, a robust professional class, and an increasing number of service workers. But it was blue collars that dominated the scene. Manufacturing accounted for well over half of all Milwaukee employment until the sharp decline of the 1930s. In 1929, on the eve of the Depression, the city had the second-highest concentration of industry in urban America.[19] “Milwaukee is a manufacturing city,” crowed industrialist Otto Falk. “The crowning glory of its activities consists of a forest of factory chimneys rather than in modern skyscrapers. It is a monster workshop whose products go to the four ends of the world.”[20]

One corollary of Milwaukee’s status as a “monster workshop” was, beginning in the 1930s, unionization on the large scale. The Wagner Act and other New Deal measures adopted to halt the nation’s economic collapse helped make Milwaukee a particular stronghold of organized labor.[21] The complementary combination of a worker-oriented government and union-oriented workplaces endured through the privations of the late 1930s, the pressures of the 1940s, and the runaway prosperity of the postwar decades.

Despite periodic downturns in the business cycle, it was not until the recession of the early 1980s that Milwaukee began to shed its industrial character. The metropolitan area lost more than 25 percent of its manufacturing jobs between 1979 and 1983.[22] Allis-Chalmers, the largest provider of those jobs in Wisconsin, went bankrupt in 1987, and some of its former erecting shops were converted to strip malls. As deindustrialization gathered steam, the nature of work in Milwaukee changed again. Heavy industry did not wither away—local firms still supplied the world with everything from motorcycles to mining equipment—but manufacturing plummeted from 39 percent of metro-area employment in 1967 to less than 15 percent in 2014. Even at that reduced level, Milwaukee retained the second-largest concentration of manufacturing jobs in urban America; deindustrialization was clearly a national phenomenon.[23]

With factory work in shorter supply, service jobs moved into the lead, outpacing manufacturing for the first time in 1986.[24] Aurora Health Care replaced Allis-Chalmers as the region’s largest private employer, and its executives moved into the former headquarters of the Heil Company, a manufacturer of truck bodies that had relocated to Tennessee.[25] A high school diploma and a strong back were no longer enough to land a family-supporting job. Leading local employers—firms like Johnson Controls, Northwestern Mutual, Kohl’s, Metavante, and the Manpower Group—placed an increasing emphasis on knowledge, typically in the form of a post-secondary degree. Milwaukee’s work options, like America’s, gravitated to two extremes: well-paid knowledge positions and low-wage service jobs, with a widening gap between them.

One industrial landmark embodies the current state of work in Milwaukee. A largely unionized work force, nearly 7,000 employees strong in the late 1960s, turned out switches, starters, relays, and timers at the Allen-Bradley plant on S. First Street for more than a half-century. The company became Rockwell Automation after a $1.65 billion buyout in 1985. Like so many other manufacturers, Rockwell moved production to lower-wage locales across the country and around the world. The last union worker left the South Side plant in 2010. The building remains busy as Rockwell’s headquarters, but nothing is made there anymore. Its thousands of employees spend their days designing, selling, supporting, computing, and managing—everything but manufacturing.[26] The iconic Allen-Bradley clock, largest in the western hemisphere, looks out over a post-industrial landscape that the company’s founders and early workers would find astonishing. Where will work reside in the landscape of future Milwaukee? That remains a vexingly open question.

Footnotes [+]

- ^ Frank Flower, History of Milwaukee, Wisconsin (Chicago: Western Historical Company, 1881), 422.

- ^ Helen Hornbeck Tanner, ed., Atlas of Great Lakes Indian History (Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 1987), 13-28.

- ^ “Antoine le Clair’s Statement,” Collections of the State Historical Society of Wisconsin, vol. 11 (Madison, WI: The Society, 1888), 240.

- ^ Charles E. Brown, “Archaeological History of Milwaukee County,” The Wisconsin Archeologist 15, no. 2 (July 1916): 24-25, 76-79, 80-81.

- ^ Joseph Schafer, Four Wisconsin Counties: Prairie and Forest (Madison, WI: State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1927), 13.

- ^ Milwaukee Sentinel, December 9, 1894.

- ^ Schafer, Four Wisconsin Counties, 129.

- ^ Schafer, Four Wisconsin Counties, 119.

- ^ Quoted in John Gregory, History of Milwaukee, Wisconsin, vol. 1 (Chicago: S.J. Clarke Publishing Co., 1931), 86-88.

- ^ Kathleen Neils Conzen, Immigrant Milwaukee, 1836-1860 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1976), 69.

- ^ James S. Buck, Pioneer History of Milwaukee, vol. 1, rev. ed. (Milwaukee: Swain & Tate, 1890), 291.

- ^ Milwaukee Sentinel, January 5, 1872.

- ^ Bernhard C. Korn, The Story of Bay View (Milwaukee: Milwaukee County Historical Society, 1980), 55-56, 83, 114.

- ^ Milwaukee Sentinel, September 25, 1881.

- ^ Emil Seidel, “Sketches from My Life” unpublished memoir, (1938), Archives Department, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Libraries.

- ^ Henry Casson, “Uncle Jerry”: The Life of Jeremiah M. Rusk (Madison, WI: J.W. Hill, 1895), 208-209.

- ^ Korn, The Story of Bay View, 82-90; Thomas W. Gavett, Development of the Labor Movement in Milwaukee (Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press, 1965), 56-65.

- ^ Gavett, Development of the Labor Movement in Milwaukee, 68-75.

- ^ Bayrd Still, Milwaukee: The History of a City (Madison, WI: State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1948), 476.

- ^ 1911 scrapbook, Otto Falk papers, Milwaukee County Historical Society.

- ^ Still, Milwaukee, 496.

- ^ Metro Milwaukee 1998 Economic Fact Book (Milwaukee: Metropolitan Milwaukee Association of Commerce, 1998), C-4.

- ^ Metro Milwaukee 1998 Economic Fact Book, C-6; Milwaukee Commerce [Metropolitan Milwaukee Association of Commerce] (Summer 2015): 6-9.

- ^ Metro Milwaukee 1998 Economic Fact Book, C-6.

- ^ Milwaukee Sentinel, June 24, 1993.

- ^ Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, August 1, 2010.

For Further Reading

Gurda, John. 1999. The Making of Milwaukee. Milwaukee: Milwaukee County Historical Society.

0 Comments

Please keep your community civil. All comments must follow the Encyclopedia of Milwaukee Community rules and terms of use, and will be moderated prior to posting. Encyclopedia of Milwaukee reserves the right to use the comments we receive, in whole or in part, and to use the commenter's name and location, in any medium. See also the Copyright, Privacy, and Terms & Conditions.

Have a suggestion for a new topic? Please use the Site Contact Form.